出处:《Handbook of Research on the Global Impacts and Roles of Immersive Media》

标题:Immersive Storytelling: Leveraging the Benefits and Avoiding the Pitfalls of Immersive Media in Domes

作者:Michael Daut, Independent Researcher, USA

翻译:Horace Lu

(注:键盘快捷键“w”或左侧菜单右上角按钮,可切换文章列表视图与大纲视图)

- 摘要 ABSTRACT

- 简介 INTRODUCTION

- 全景球幕画布的独特性 UNIQUENESS OF THE FULLDOME CANVAS

- 叙事工具 STORYTELLING TOOLS

- 全景球幕影片制作的挑战 FULLDOME FILMMAKING CHALLENGES

- 数字全景球幕中的关键视觉叙事工具 KEY VISUAL STORYTELLING TOOLS FOR DIGITAL FULLDOME

- 有效的全景球幕叙事示例及分析 EXAMPLES AND ADVANTAGES OF EFFECTIVE FULLDOME STORYTELLING

- 如何在全景球幕上讲故事 HOW TO TELL STORIES ON THE DOME

- 让画面说话 Show, Don’t Tell

- 构思客观与主观场景 Design Objective and Subjective Scenes

- 精心设计时长较长、复杂度较高的镜头 Choreograph Longer Shots with Higher Degrees of Complexity

- 以媒介特性和观众体验为核心进行剪辑 Edit with the Medium and Audience in Mind

- 发挥球幕变化自身的能力 Leverage the Dome’s Ability to Transform Itself

- 最重要的事 Most Important

- 影片示例 Examples

- 技巧与建议 Tricks and Tips

- 结论 CONCLUSION

- 参考文献 REFERENCES

摘要 ABSTRACT

This chapter compares and contrasts the development of traditional cinema and fulldome cinema, describing the way their origins shaped not only their current success and potential as unique cinematic mediums, but also how their cinematic languages developed. There is a vastly different approach to storytelling that filmmakers must understand when creating shows for immersive digital dome theaters versus the approach they would take to tell stories in a traditional film. This chapter identifies key differences between cinema and fulldome and provides a primer for immersive storytelling on the dome from understanding the technology to understanding how most effectively to use the strengths of fulldome while avoiding its weaknesses. Ultimately, this discussion is designed to help creative artists become more effective immersive filmmakers for the fulldome canvas.

本章探讨了传统电影与 全景球幕(fulldome) 电影的发展历程,展示了它们的起源如何影响了各自作为独特电影形式的成功与发展潜力,以及它们各自独有的电影语言是如何形成的。电影制作人在创作针对沉浸式数字球幕影院的作品时,所采取的叙事方法与传统电影中的叙事方法大相径庭。本章不仅指出了传统电影和全景球幕之间的主要差异,还为在球幕上实现沉浸式叙事提供了基础指南,从理解这一技术本身,到如何有效利用全景球幕的特点,同时规避其不足。这一系列讨论旨在助力创意人才成长为更加出色的全景球幕沉浸式电影创作者。

简介 INTRODUCTION

Modern society is experiencing an explosion of immersive media in a nearly overwhelming number of forms: Virtual Reality (VR) that requires a headset that feeds 360º imagery in the user’s eyes and pours immersive audio into their ears; Augmented Reality (AR) that creates visual and auditory overlays on top of reality using a smart phone or a semi-transparent pair of glasses; Mixed Reality (MR), that uses a combination of VR and AR to create new and unexpected experiences through a headset that can change from fully transparent to fully opaque based on the content creator’s design. Then there are hybrid forms of immersive media that blend theatrical stagecraft with a VR system that allows free roaming through physical spaces with walls people can see virtually and touch in reality, props they can use, and other tactile sensations that powerfully blur the lines between virtual and reality. These are just some examples of immersive media that involve some sort of device that the audience must either use or wear, and more times than not, these “vehicles to immersion” create a sense of isolation, not a shared community experience.

在当今社会,沉浸式媒体正以一种几乎令人应接不暇的形式迅速发展:虚拟现实(VR)需要用户戴上头显,360 度的影像直接呈现在眼前,沉浸式的音频环绕耳边;增强现实(AR)通过智能手机或半透明眼镜,在现实世界之上叠加视觉和听觉效果;混合现实(MR)则结合了 VR 和 AR 的特点,通过可根据内容创作者的设计从完全透明变为完全不透明的头显,创造出新颖而出人意料的体验。此外,还有将戏剧舞台技术与 VR 系统结合的混合型沉浸媒体,它允许人们在有实体墙壁的物理空间中自由漫游,使用可在现实中触摸到的道具,以及其他强烈的触觉感受,极大地模糊了虚拟与现实之间的界限。这些仅仅是沉浸式媒体的一部分例子,它们通常需要观众使用或佩戴某种设备,而更多时候,这些“沉浸之舟”带来的是孤立感,而非共享的集体经验。

On a more basic level there is 3D stereo technology that exists in cinema, VR, home theater, video games, lenticular stereo printing, giant screen theaters, and even giant 3D dome theaters to add visual depth to the experiences. In a completely different type of experience, interactive media platforms like Twitch add to the viewer’s sense of agency and therefore immersion.

在更为基础的层面上,3D 立体技术已经存在于电影院、虚拟现实(VR)、家庭影院、电子游戏、立体印刷、巨幕影院,甚至是巨型 3D 球幕影院等媒介中,为观众带来了视觉深度上的增强体验。像 Twitch 这样的互动媒体平台则提供了另一种完全不同的体验,增强了观众的主体感(agency)和沉浸感(immersion)。

These “new media” experiences have brought with them new ways of telling stories and a new type of cinematic and aesthetic language that creatives and consumers alike are still trying to understand and unravel. New media storytellers are experimenting with new ways of immersive expression and developing and inventing a new lexicon of techniques and understanding how to speak this immersive visual language. It is an exciting time as creatives are blazing a trail through this largely undiscovered country. Exploring the art of immersive storytelling opens a deep well that branches in nearly infinite directions that would overwhelm this chapter and spill over into a series of books.

这些“新媒体”体验带来了全新的叙事手法和一种电影美学语言,无论是创作者还是观众,都在努力探索和解读。新媒体的叙事者们正在尝试新的沉浸式的表达方法,并开发、创造一套新的技术词汇,学习如何运用这种沉浸式的视觉语言。这是一个激动人心的时代,因为创意人士正在这片广袤的、未被开垦的领域中开拓前行。探索沉浸式叙事的艺术就像打开了一眼深不见底的源泉,它的分支几乎无穷无尽,足以填满本章节并延伸成一系列书籍,让人应接不暇。

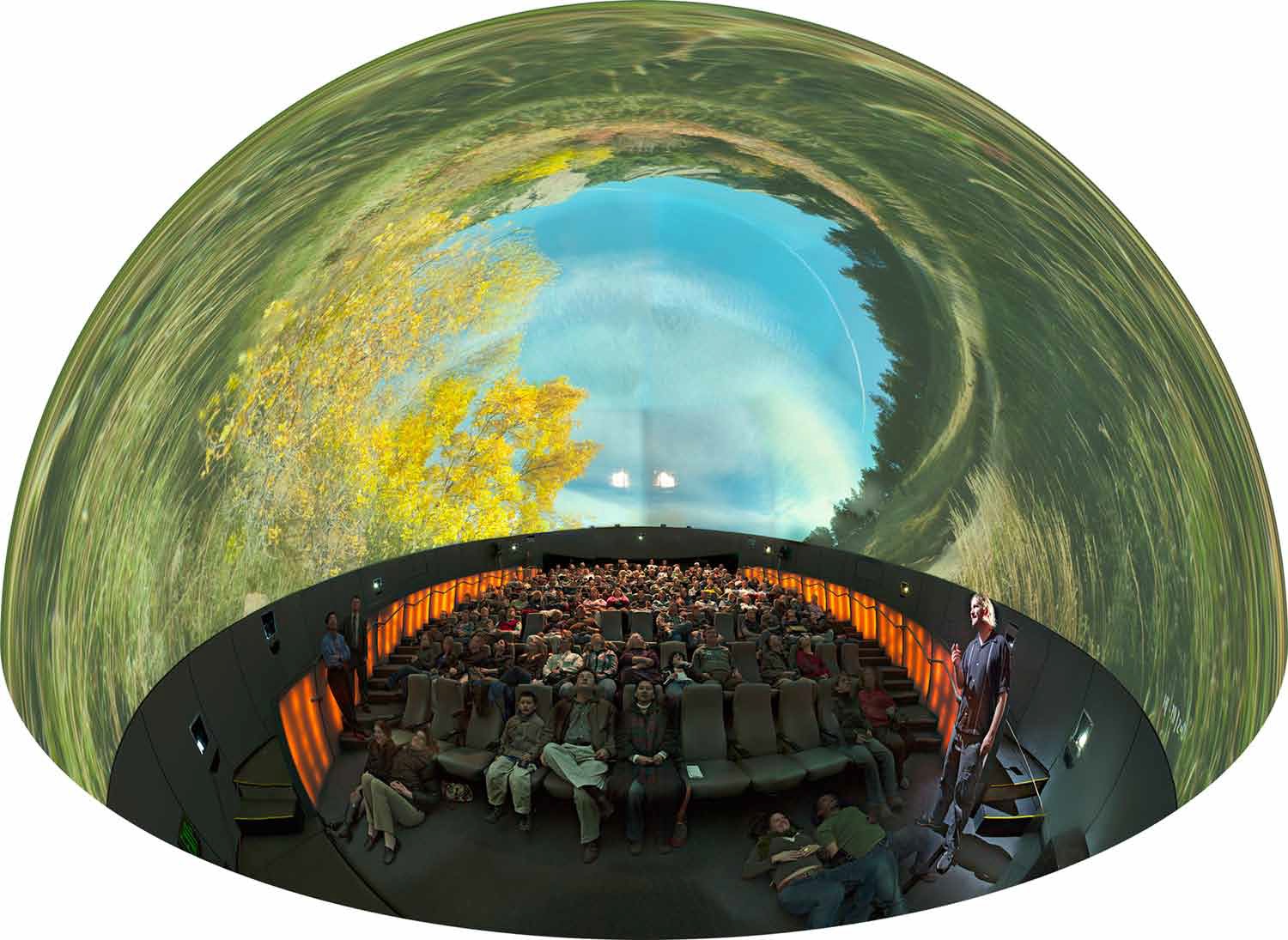

This chapter focuses on a specific type of immersive medium: digital fulldome theaters (Figure 1). From their origins as planetarium spaces to their continuing growth into VR Theaters of the future, this exciting medium has developed its own cinematic language that is part traditional cinema, part live theater, and a lot of something magical that when leveraged effectively can transport audiences as a small community into shared virtual experiences. Technological advancements and system features still impact digital domes as much as the format’s differences from traditional cinema. How has cinematic language developed in traditional cinema, and how has it formed in digital immersive domes? How can these languages be the same? How must they be different? Are immersive digital fulldome theaters effective spaces for storytelling, or are these spaces best used for documentary-style programs and purely educational experiences? These questions are only the jumping-off points for this fascinating exploration.

本章将着重探讨一种特定的沉浸式媒介:数字全景球幕影院(digital fulldome theaters,见图 1)。它们从最初的天文馆空间发展至今,正不断进化成为未来的虚拟现实影院。这种令人兴奋的媒介已经形成了自己独特的电影语言,既继承了传统电影的精髓,又融入了现场演出剧院的活力,还包含了许多神奇的元素。当这些元素被有效利用时,能够将观众作为一个紧密的社群带入共享的虚拟体验之中。技术的进步和系统的特性对数字球幕的影响,与它们和传统电影格式的差异同样重要。传统电影中的电影语言是如何发展起来的?在数字沉浸式球幕中,这种语言又是如何形成的?这两种语言有何相似之处?它们又为何必须有所区别?沉浸式数字全景球幕影院是讲述故事的有效场所,还是更适合于纪录片风格的节目和纯粹的教育体验?这些问题仅仅是这场引人入胜的探索的起点。

Figure 1. Inside a digital fulldome theater with immersive visuals

Source: © 2019 Greg Downing, Hyperacuity.com. Used with permission.

电影语言的发展 The Development of Cinematic Language

Modern cinema was born with the invention of the motion picture camera, and as often happens, many pieces of this technology were being developed simultaneously and independently by a number of inventors across the world. It is therefore difficult to pinpoint exactly who invented the motion picture camera, although most historians attribute this honor to American innovator, Thomas Edison, who incidentally would have willingly accepted this attribution. The truth of the matter is more complicated, of course, with Edison’s Kinetograph, motion picture camera, built upon the work of early pioneers, Francis Ronalds, Wordsworth Donisthorpe, Louis Le Prince, William Friese-Greene, and William Kennedy Laurie Dickson. Even the exact year the world-changing camera came into being is up for debate. For further background on the story behind the creation of the motion picture camera, explore the many resources listed in the Additional Reading section at the end of this chapter.

现代电影的诞生与电影摄影机的发明密不可分。与其他许多技术的发展类似,这项技术的多个组成部分是由世界各地的多位发明家同时且独立开发的。因此,要明确指出谁是电影摄影机的发明者是非常困难的,尽管大多数历史学家都将这一荣誉归于美国发明家托马斯·爱迪生,而爱迪生本人也乐于接受这一名号。当然,事实的真相要复杂得多,爱迪生的“电影机”(Kinetograph),一种早期活动影像摄影机,是在弗朗西斯·罗纳兹、沃兹沃斯·多尼斯特霍普、路易·勒普林斯、威廉·弗里斯-格林、威廉·肯尼迪·劳瑞·迪克森等早期先驱者的工作基础上构建的。关于这项改变世界的摄影机发明,其具体问世年份也存在争议。要了解更多关于活动影像摄影机发明背后的故事,可以探索本章末尾的“参考文献”部分列出的众多资源。

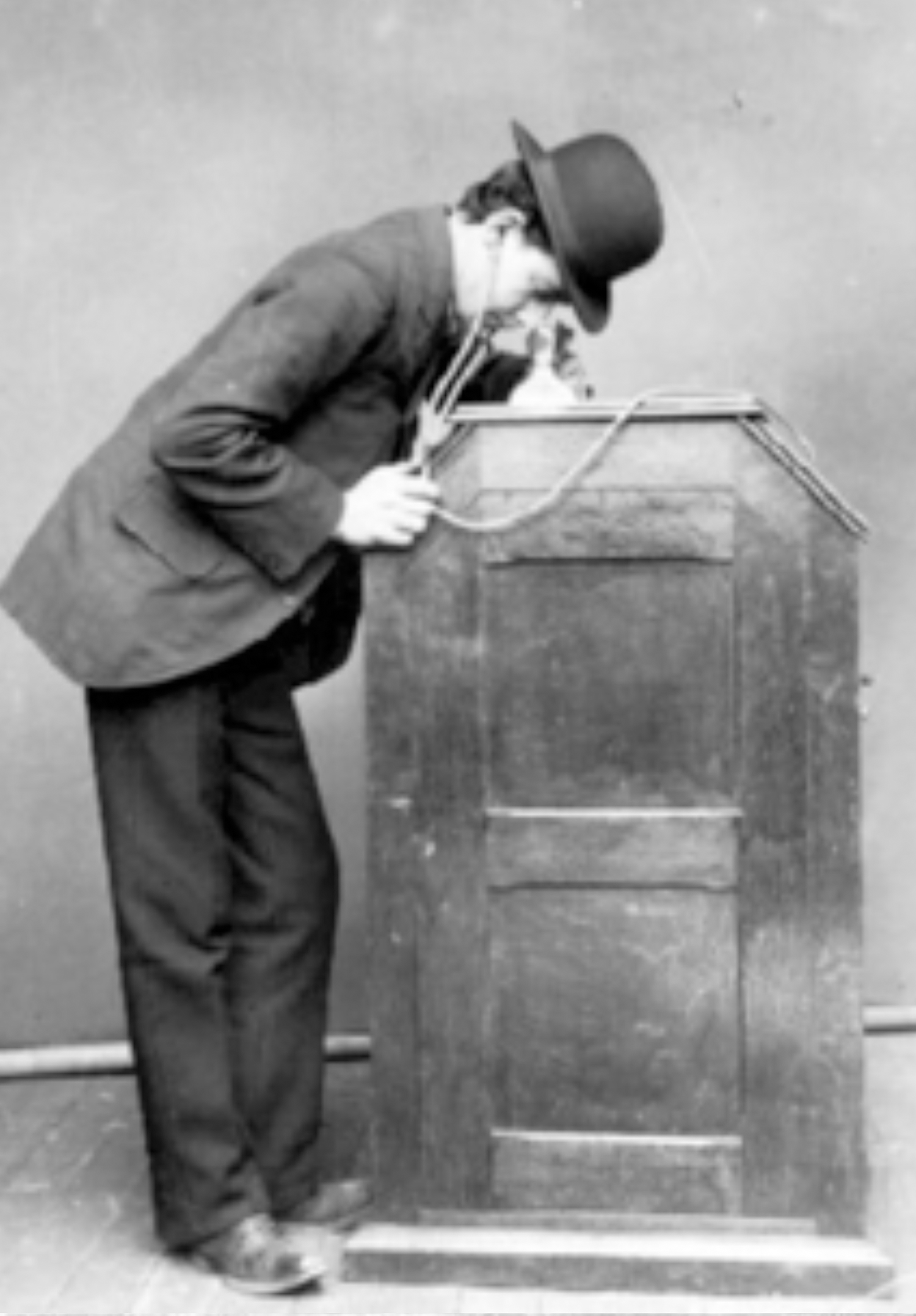

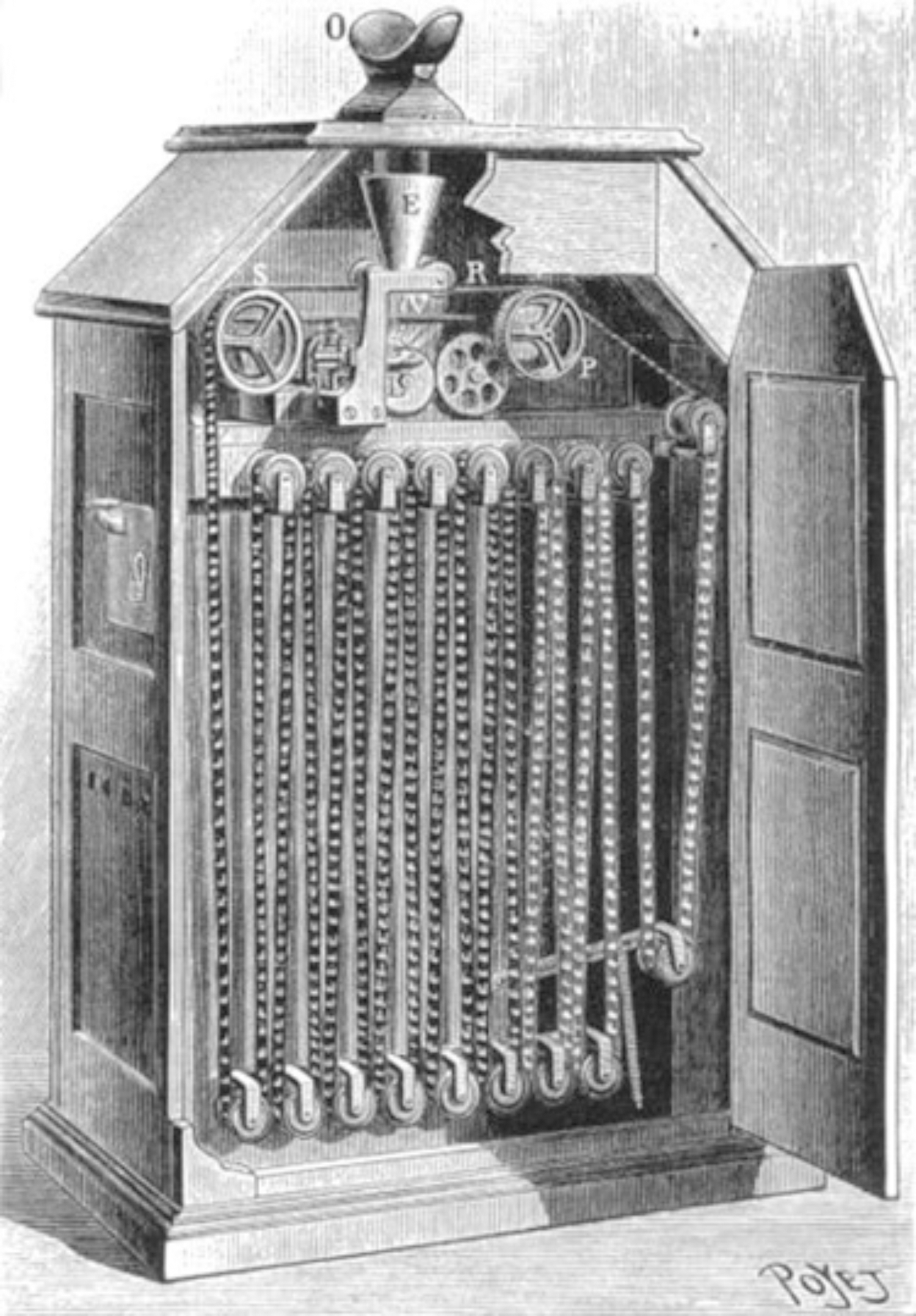

Regardless of its specific origins or authorship, in 1891 or 1892, the motion picture camera ushered in the age of cinema. Cinema exhibition started with Edison’s Kinetoscope (Figure 2): a mechanical device in which one person at a time would look through an eyepiece or “peephole” at the top to view the images printed sequentially on a strip of film. Sprocket holes along the film’s edges allowed the film to be pulled through the device across an illuminated image plate below the peephole. A high-speed shutter hid the transition between frames, completing the illusion of movement. Later the Lumi è re brothers would transform the Kinetoscope into the Cinématographe, the first motion picture projector, allowing an entire audience to view the film at once (Library of Congress, n. d.).

无论具体的起源或发明者是谁,在 1891 年或 1892 年,活动影像摄影机都开启了电影的时代。电影的放映始于爱迪生的“电影视镜”(Kinetoscope,见图 2)。这是一种机械装置,一次只有一个人通过顶部的“观影孔”观看连续印在一卷胶片上的图像。胶片的边缘有一排排小孔,这些小孔让胶片能顺利地通过放映机,跨过一个位于观影孔下方的发光图像板。高速快门隐藏了胶片格与格之间的转换,制造了运动的错觉。后来,卢米埃尔兄弟将“电影视镜”改造为“电影放映机”(Cinématographe),这是第一台活动影像放映机,允许整个观众群体同时观看电影(美国国会图书馆,无日期)。

Figure 2: A person watching a movie with Edison’s Kinetoscope

Source: Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3. The interior of Edison’s Kinetoscope showing the film path

Source: Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons

It took over two decades for filmmakers to truly understand and exploit its visual language. D.W. Griffith was one of the early masters of visual cinematic storytelling, using the close-up and careful editing to build the experience shot by shot. Legendary pioneering filmmakers such as Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Cecil B. De Mille, and others further contributed their legerdemain to advance the art. In step with (or more accurately, many steps behind) developing creative and aesthetic techniques, the technology itself advanced, sometimes at a snail’s pace; other times blindingly fast, creating an interdependency that exists to this day. Filmmakers developed their stories within the confines of the technology while pushing diligently against technology’s limits. At the same time, the inventors both responded to the creative needs and leveraged new, even groundbreaking developments to reinvent the process of motion picture image capture and exhibition (and all the steps in between) over and over again with nearly relentless fervor. In the same way, filmmakers would leverage these new innovations to further elevate visual storytelling and define new ways to create movies in the ever-changing technological landscape. This interdependent growth cycle between art and technology is not unique to cinema. The same patterns can be seen in computer technology, science, engineering, music, even accounting and finance. Technology creates opportunity; users drive technology; technology advances creating new opportunities; users find new applications and drive technology further; technology advances again, and the cycle goes on indefinitely. The cycle itself is not as crucial to this discussion as is the interdependence of art and technology. They cannot be separated, and they enable one another. Just as oil paints as a medium influence and affect the outcome of the art on the canvas, so the technology of cinema affects those who paint with its cinematic language. The creation of the art must leverage the available tools and the strengths and limitations of the medium to harness its full potential. This required deep understanding and experience on the part of the artist.

电影人花了二十多年的时间才真正理解并开始应用电影的视觉语言。D.W. 格里菲斯是视觉电影叙事的早期大师之一,他运用特写镜头和精心的剪辑构建逐个镜头的体验。巴斯特·基顿、查理·卓别林、塞西尔· B ·德米尔等传奇的先驱电影人进一步贡献了他们的巧妙手法,推动了这门艺术的发展。随着创意和审美技巧的发展,技术也在不断进步,但这种进步有时非常缓慢,有时则是突飞猛进。正是这种时而缓慢时而迅速的发展,构建了创意与技术之间持续至今的相互依存关系。电影人在技术的局限下拓展他们的故事,同时孜孜不倦地挑战技术的极限。与此同时,发明家们一方面响应创意需求,另一方面也带着不懈的热情,利用新的、甚至是开创性的进展,一次次地重新发明活动影像的拍摄和放映流程(以及两者之间的所有步骤)。同样地,电影人也会利用这些创新来进一步提升视觉叙事,并在不断变化的技术环境中定义制作电影的新方法。艺术与技术的这种相互依赖的增长周期并不是电影独有的,在计算机技术、科学、工程、音乐,甚至会计、金融等领域,都可以看到同样的模式。“技术创造机会;用户推动技术;技术进步创造新机会;用户发现新应用并进一步推动技术;技术再次进步”,这个周期无限循环。与这种周期相比,艺术与技术的相互依赖对于本讨论更为关键,它们不可分割、相互促进。正如油画颜料作为绘画的媒介会影响画布上艺术作品的表现力一样,电影技术同样影响着那些运用电影语言进行创作的艺术家。艺术创作必须利用可用的工具及媒介的优势和局限来发挥其全部潜力,这需要艺术家对此有深刻的理解和丰富的经验。

数字球幕系统的发展 The Development of Immersive Digital Dome Systems

Just as motion pictures, immersive dome systems began with analog technology. In 1923 the Zeiss Corporation in Jena, Germany developed a revolutionary optical mechanical projection device, a metal sphere studded with lenses and a cylindrical appendage that extended underneath, affectionately called, The Wonder of Jena, that could realistically reproduce the starry night sky. This device required a new physical structure and projection surface that approximated the apparent shape of the sky overhead. A large hemispherical dome, 360 ° around by 180 ° high became the obvious choice (Lambert, 2012).

正如电影技术起步于模拟技术一样,沉浸式球幕系统也是从模拟技术开始的。1923 年,位于德国耶拿的蔡司公司(Zeiss Corporation)开发了一种革命性的光学机械投影装置——一个布满透镜的金属球体,下面延伸出一个圆柱形的附属物,被亲切地称为“耶拿奇迹”,它能真实地再现繁星点点的夜空。这个装置需要一种新的物理结构和投影表面,来模拟头顶上天空的形态。一个巨大的、360 度环绕的、高 180 度的半球形穹顶,成为了显而易见的选择(Lambert, 2012)。

The world’s first planetarium opened at the Deutsche’s Museum in Munich, Germany in 1925 with the first Carl Zeiss optical mechanical star projector. The projector used light inside of a mechanism that could project points of light that replicated the starry sky as seen from Earth, enabling them to move across the sky as night transitioned to day and back again into night. It could even adjust its orientation to show the accurate night sky from any location on Earth. This optical mechanical projector also featured planet projectors that through precise mathematical calculations could mirror the forward and retrograde movement of planets through the night sky. This technology caught worldwide attention, inspiring a generation of astronomers and science educators. The first planetarium in the US, the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, opened its planetarium in 1930, with other, now legendary planetariums, like the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles opening shortly thereafter (Marche, 2005).

世界上第一个天文馆于 1925 年在德国慕尼黑的德意志博物馆(Deutsche’s Museum)开幕,配备了第一台卡尔·蔡司光学机械星空投影仪(Carl Zeiss optical mechanical star projector)。这台投影仪使用装置内部的光源,能够以投影光点的形式模拟地球视角所见的星空,并展现其从昼到夜、从夜到昼的运动轨迹。它甚至可以调整方向,从而显示在地球上任何地点看到的准确夜空。这款光学机械投影仪还配备了行星投影仪(planet projectors),通过精确的数学计算,能够模拟行星在夜空中的顺行和逆行运动。这项技术引起了全球的关注,激励了一代天文学家和科学教育工作者。美国的第一个天文馆——芝加哥的阿德勒天文馆——于 1930 年开放,而其他传奇天文馆,如纽约的美国自然历史博物馆、洛杉矶的格里菲斯天文台等,也相继在不久后开放(Marche, 2005)。

It goes without saying that Carl Zeiss and other companies that followed, designed and built domes with the express purpose of showing audiences the wonders of the night sky. These theaters provided astronomy education spaces where people could learn about and identify constellations, planets, and seasonal changes in the sky. The original theater and seating design that supported this purpose consisted of a hemispherical dome screen hung directly above the audience with its base completely parallel to the ground (with no tilt forward or backward in any direction). The audience sat in concentric rows with their backs to the outside walls, each guest facing into the center of the theater where the optical mechanical projector resided. This orientation allowed guests to view the night sky in all directions simultaneously while highlighting the magnificent star projector as the centerpiece to the experience (Figure 4).

显然,卡尔·蔡司与其他后继公司设计并建造球幕的明确目的,是向观众展示夜晚星空的奇观。这些影院提供了天文学的教育空间,人们可以在这里学习并认识星座、行星和天空的季节变化。为了支持这样的原初目的,最初的球幕影院及其座位采取了特殊的设计,包括一个直接悬挂在观众头顶的半球形穹顶屏幕,其底部完全平行于地面,在任何方向上都没有向前或向后倾斜。观众坐在一排排同心圆的座位上,每名观众都背对外墙,面向影院中心,即面向光学机械投影仪所在的位置。这种布局让观众可以同时向所有方向观看夜空,同时将壮观的星空投影仪凸显出来,作为体验的中心(见图 4)。

Figure 4. Inside a concentric planetarium with a non-tilted 180º dome and star projector

Source: Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons

The modern planetarium was born (incidentally, only about 40 years after the birth of the motion picture camera). This new medium that was purpose-built for teaching astronomy would embark on its own wild ride and hard-fought path to be a legitimate cinematic and immersive medium in its own right, and the battle has only begun.

由此,现代天文馆诞生了(顺便一提,这大约是在活动影像摄影机诞生 40 年后)。这种最初专门为天文学教学而建造的新媒介,将踏上一条充满挑战和斗争的发展之路,努力成为一种独立的、合法的电影和沉浸式体验媒介,而这一进程才刚刚拉开序幕。

Even with the star projector’s exquisite ability to recreate the stars and planets of the night sky, the instrument could only depict stellar observation from the surface of earth. The audience could never take off into space and fly through the stars. Because star projectors were large mechanical devices, they could only move the night sky at relatively slow speeds to simulate Earth’s rotation and the eventual sunrise.

虽然星象投影仪具有重现夜空中的恒星和行星的精妙能力,但这种设备只能描绘从地球表面观测到的星空,而无法让观众飞入太空,穿越星辰。因为星象投影仪是大型机械设备,它们只能以相对较慢的速度展现夜空的移动,模拟地球的自转和最终的日出。

In the early 1970’s, Ivan Dryer created Laserium, a visual music experience for planetarium domes. Ivan and his team created a custom laser projector that could be preprogrammed and choreographed to a musical soundtrack and performed live across the dome’s interior in front of an audience. Laserium stepped into history at the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles on November 19, 1973. For the first time pure entertainment shows entered planetarium domes, and the impact of Laserium continues to inspire producers and inspire new creative uses for the dome’s hemispherical canvas (Ehrman, 2002).

在 20 世纪 70 年代初,伊凡·德赖尔(Ivan Dryer)创造了 Laserium,这是一种为天文馆球幕创造的视觉音乐体验。伊凡和他的团队制造了一种定制的激光投影仪,可以预编程并编排成音乐声轨,在观众面前的球幕内部现场表演。Laserium 于 1973 年 11 月 19 日在洛杉矶的格里菲斯天文台正式亮相,这是第一次有纯娱乐节目在天文馆球幕中呈现。Laserium 的影响仍在不断激励着电影制作人,利用这种半球形的巨幕寻找新的创意路径(Ehrman, 2002)。

Then in the early 1980’s something revolutionary (and at the time somewhat primitive by today’s standards) happened. Evans & Sutherland (E&S) a company based in Salt Lake City, Utah largely known for their pioneering work in computer graphics, introduced a digital star projector called Digistar, and the planetarium changed forever, but certainly not overnight. In fact, the planetarium is still in the process of changing to this day. Digistar introduced two significant groundbreaking capabilities: 1) the ability to lift off of Earth and fly through the stars (and view them from essentially any point in the known universe and at any point in history); 2) the ability to create vector graphics allowing the display of any sort of wireframe computer graphics imaginable. These digital tools expanded the types of experiences that were possible inside planetarium domes.

随后,在 20 世纪 80 年代初发生了一项革命性的进展,尽管按照今天的标准来看仍有些原始。位于犹他州盐湖城的 Evans & Sutherland(E&S)公司,以其在计算机图形学方面的开创性工作而闻名。该公司推出了一款名为 Digistar 的数字星象投影仪,自此永远改变了天文馆的形态。不过这种改变并非发生在一夜之间,实际上天文馆直到今天仍在经历着变革。Digistar 引入了两项重大的突破性能力:(1)能够离开地球,穿越星空,从已知宇宙的任意位置观察星辰,看到它们在历史上任意时刻的状态;(2)能够创建矢量图形,允许呈现创作者能想到的任何基于线框的计算机图形。这些数字工具扩展了天文馆球幕内可能的体验类型。

Because of Laserium and Digistar’s paradigm shifts, the dome theater started to become more than just a planetarium, but its metamorphosis would be slow: very, very slow.

Laserium 和 Digistar 所带来的范式转变,使得球幕影院开始不再只承担天文馆的功能。但这个蜕变过程却十分缓慢,非常、非常缓慢。

The 1990’s introduced yet another giant leap forward: fulldome video (Figure 5). The concept was straightforward and ingenious. Take a number of video projectors—initially six—install them in a circular arrangement at the bottom edge of the dome screen and project imagery from these projectors across the dome to create one fulldome video display. These projected images would overlap each other, creating regions where the images could be blended together. Precise, painstaking alignment of the blended images would create the illusion of a single fulldome video. A cluster of PCs or a real-time computer image generator (essentially a powerful custom computer built for flight simulation) processed a sequence of circular fisheye images into the system, sliced into tiles that would synchronize and feed each individual projector, allowing video to display across the fulldome canvas.

20 世纪 90 年代,全景球幕视频的出现标志着另一场巨大的飞跃(见图 5)。这个概念简单而巧妙:使用几台(最初是六台)视频投影仪,将它们以圆形排列安装在球幕的底部边缘,从这些投影仪投射图像到球幕上,从而显示一个完整的全景球幕影像。这些投影的图像会相互重叠,形成可以混合图像的区域。通过精确、细致地调整图像的融合与边缘对齐,就可以创造出一个完整的全景球幕视频的幻觉。一系列的个人电脑或特制的实时图像生成器(这是一种专为飞行模拟开发的高性能计算机)被用于处理圆形的鱼眼效果图像,并将这些图像分割成多个小块。随后,分别将这些小块图像同步传送给各个投影机,从而在整个球幕上实现视频的完整显示。

Figure 5. Inside a digital fulldome theater

Source: Adam Kozak distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license

Once fulldome video existed, dome productions could tell more immersive and sophisticated visual stories, but the fact that domes were nearly exclusively found in planetariums, most fulldome content stayed within the astronomy genre. This is a critical reason that it has been (and continues to be) difficult for fulldome films to break free from their astronomical origins and become more mainstream. Theater design shifted from domes that were parallel to the ground with omnidirectional seating to domes that tilted forward in front of the audience with unidirectional seating that faced the front of the dome tilted down anywhere from 10º to 30º. This has produced a daunting inconsistency in theater layout, dome tilts, projector resolution, placement, quality, and seating configurations, which presents significant challenges for producers who hope that their content will look equally good in all venues.

在全景球幕视频诞生后,球幕影片便可以讲述更具沉浸感与视觉复杂性的故事了。但因为球幕几乎只存在于天文馆中,大多数全景球幕内容仍然停留在天文学领域,这是全景球幕影片难以摆脱其天文学起源、成为更主流媒介的关键原因。球幕影院的座位设计也发生了变化,从与地面平行的全向座位,转变为面向球幕前端倾斜(倾角从 10º 到 30º 不等)的单向座位,这导致了影院布局、球幕倾斜度、投影仪分辨率、投影位置、画面质量、座位配置等参数的千差万别。对于制作人而言,要想让影片在所有球幕场馆中呈现同样出色的效果,就需要面对这种不一致性带来的巨大挑战。

Today’s advancements have dramatically improved image quality in the theaters. Auto-alignment and auto-blending technologies have allowed even more projectors to be tiled together across the screen and look visually seamless, as if projected from a single source. The most advanced domes use laser video projection and enough 4K projectors to create a fulldome canvas that is over 8192 x 8192 pixels (over 64,000,000 pixels). At the time of writing, the most compelling new technology to be introduced is a self-illuminating dome constructed of LED tiles, eliminating the need for video projection.

如今,技术的进步已经显著提高了球幕影院中的影像质量。自动对齐和混合技术可以将更多台投影仪的画面拼接在球幕上,达到视觉上的无缝衔接,就像从单一源投射出来的一样。最先进的球幕采用激光视频投影技术,将足够多的 4K 投影仪组合起来,创造一个超过 8192 x 8192 像素(总计 64,000,000 像素以上)的全景球幕画布。在撰写本文时,最引人注目的新技术是由 LED 模块构成的自发光球幕,这种技术使得投影机不再是必需品。

Fulldome’s planetarium origins and the fact that almost its entire network of existing theaters exists within planetariums and science centers have largely prevented content to break free from a science education focus to general entertainment. Planetariums’ general lack of marketing budget and lack of budget in general often prevents them from being able to afford higher quality shows. The low revenue stream from theaters that license fulldome shows has kept production budgets low, maybe 1% or less of the typical budget spent on a Hollywood film.

全景球幕起源于天文馆的历史,导致当前几乎所有的球幕影院都存在于天文馆和科技馆,这在很大程度上阻碍了球幕内容从科教题材转向大众娱乐题材。天文馆普遍缺乏预算(特别是营销预算),这也阻碍了它们购买更高质量的影片。由于球幕影院获得的收入较低,全景球幕影片的制作预算也保持在很低的水平,可能只有典型好莱坞电影预算的 1% 或更少。

Still, the powerful immersive nature of the medium is propelling it forward into new types of content and into new and unexpected venues including themed entertainment, pop up experiences, concerts, theatrical performances, and touring shows.

然而,这种媒介所提供的强大无比的沉浸式体验,使得它不仅拓展到了新的内容领域,也进入了多样化和超乎想象的场合,包括主题公园娱乐、快闪活动、音乐会、剧场演出及巡演等。

As mentioned in the introduction VR, AR, MR and most other immersive technologies require some sort of apparatus and some degree of individualized isolation for the experiences to work. Not so in fulldome. This exciting medium has the true potential to deliver on the promise of VR while remaining a communal, shared experience. Fulldome is essentially the platform for the VR Theater of today and the future. Fulldome also has the potential to attract audiences in a way that traditional cinema is struggling to maintain.

正如引言中提到的,虚拟现实(VR)、增强现实(AR)、混合现实(MR)以及其他大多数沉浸式技术,都依赖于某种设备以及一定程度的个体隔离,才能产生沉浸效果。全景球幕则不同,这一激动人心的媒介真正具有实现 VR 承诺的潜力,同时保持了一种集体的、共享的体验。就其特质而言,全景球幕是当今和未来虚拟现实影院的平台,并且有着以传统电影院难以维持的方式吸引观众的潜力。

Because of its uniqueness and its ability to exceed the power of VR, it’s important to understand the distinguishing characteristics of fulldome, its potential, and its cinematic language. The rest of this chapter is designed as a primer, of sorts for the medium and a guide to harnessing its abilities to create a powerful new form of storytelling.

正因其独特性以及超越 VR 的力量,理解全景球幕区别于传统电影的特征、潜力和电影语言是非常重要的。本章的其余部分旨在作为这种媒介的入门指南,希望能够指导读者利用全景球幕的能力创造一种强有力的新型叙事形式。

全景球幕画布的独特性 UNIQUENESS OF THE FULLDOME CANVAS

The fulldome medium itself stands at the intersection of theater and cinema, yet it is neither both nor one or the other. It is its own blended experience that can be leveraged to produce a powerful sense of presence within an immersive theater. Also, whereas VR is an individual, isolating immersive experience, akin to Edison’s Kinetoscope, fulldome is a shared audience experience more like the Lumi è re brothers’ Cinématographe motion picture projector.

全景球幕这一媒介位于剧院和影院的交叉点,它既不是剧院也不是影院,而是两者的融合体验,可以用来在沉浸式影院中产生强烈的临场感。此外,与 VR 这种类似于爱迪生“电影视镜”的个体化、孤立化的沉浸体验不同,全景球幕是一种共享的观众体验,更类似于卢米埃尔兄弟的“电影放映机”。

观看与身临其境 Looking at vs. Being Inside

Unlike traditional cinema, where the audience is looking at a screen, digital fulldome places the audience inside of the screen. Cinema uses a framed window in front of the audience to slowly invite them into the experience through emotional connection and the willing suspension of disbelief. Fulldome cinema surrounds the audience in such a way that they start inside the experience, even before the audience’s engagement can draw them in. This instant or “forced immersion” can be difficult to overcome, especially if the audience feels overwhelmed and pushes back from this intrusion. It’s the cinematic version of coming on too strong romantically. It can be uncomfortable and off-putting. More subtle techniques at the start of a fulldome film/immersive experience should be employed to create an emotional connection or conversely, a fascinating spectacle could be created that entices the audience to want to see more. A live presenter to warm up the audience or even participate in the dome show can function as the audience surrogate in the immersive presentation and bridge this gap even further. Once the audience engages in the experience, the feeling of deep immersion and sensation of simulated reality can be extraordinarily impactful.

与观众在传统电影院观看银幕不同,数字全景球幕将观众置于银幕之中。传统影院的银幕像一扇镶有框架的窗户,缓缓地吸引观众进入其世界。它依靠情感的共鸣,使观众愿意暂时放下怀疑,共同构建观看体验。相较而言,全景球幕以一种环绕观众的方式,使观众在正式参与到故事中之前,就直接置身于这一独特体验之中。这种“立即深入”或称之为“自动沉浸”的体验,对于观众来说可能是个挑战,特别是当观众感觉被压倒(overwhelmed)时,可能会本能地抵触这种突如其来的沉浸感。这种情况有点像电影中的浪漫追求来得过于强烈,可能让人感到不适和抗拒。在全景球幕电影或沉浸式体验的初始阶段,应该采用更细腻的手法来建立情感联系,或者反之,创造一个足够吸引人的视觉奇观,让观众产生继续探索的欲望。也可以引入一位现场主持人来预热观众情绪,甚至让观众参与到球幕表演当中,作为踏入这场沉浸式之旅的桥梁,进一步缩小观众与沉浸式体验之间的距离。当观众开始融入这种体验时,深度沉浸的感受和仿真现实的震撼,将会为他们留下更为深刻的印象。

临场感 Sense of Presence

The visuals that surround the audience create a strong sense of presence, simulating the sensation that the audience actually exists in the place depicted around them on the dome. This is a powerful illusion that is analogous to subjective camera in traditional cinema, where the audience is seeing through the camera as if they are participating in the scene. This effect is more powerful in immersive fulldome, since there is no perceived or implied camera. The virtual world simply surrounds the audience and transports them into the scene’s setting, much like the legendary Holodeck from Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987).

全景球幕通过环绕观众的视觉效果营造出一种强烈的临场感,仿佛观众真的置身于银幕呈现的场景之中。这种强大的幻觉堪比传统电影中的主观镜头(subjective camera),让观众感觉自己正在亲历其中。由于全景球幕影院中不存在实际或隐含的摄影机角度,这种沉浸感会更加显著。观众被虚拟世界包围,仿佛被直接带入场景设定中,这与《星际迷航:下一代》(1987)中的全息甲板(Holodeck)技术颇有几分相似。

Cinematically there are two major types of scenes in fulldome: subjective scenes and objective scenes. Subjective scenes (designed to make the audience feel as if the experience is happening to them personally) inherently play in real time, since that is the only way humans can move through time and space. Most transitions should not be used in these sequences, since there are no transitions or gaps in time or space when moving from one place to another in reality. When scene changes are necessary within subjective sequences, dips to black, or a time/space travel device, like a visual time warp, launch to light speed, or some similar visual effect, can preserve the audience’s sense of being a participant in the scene. In the early days of digital fulldome, essentially all scenes were subjective scenes. Producers were concerned about breaking the audience’s sense of presence in time and space. This greatly limited the types of storytelling that could be done and eliminated the possibility for editing and adjustments to the show’s pacing.

全景球幕电影主要分为两类场景:主观场景(subjective scenes)和客观场景(objective scenes)。主观场景旨在让观众感受到事件仿佛发生在自己身上,因而通常以实时发生的形式呈现。在这种场景下,应尽量避免使用转场效果,因为人在现实时空中的移动是连续无缝的。当需要变换场景时,可以使用淡出至黑场的效果,或采用时空旅行的视效,如视觉时间扭曲(visual time warp)或光速飞跃(launch to light speed)等,这有助于保持观众的参与感。在数字全景球幕的诞生初期,几乎所有场景都采用了主观视角,制作团队担心其他拍摄方式可能会破坏观众对时空连续性的感知。这种做法极大地限制了故事类型的多样性,并且排除了通过后期剪辑来调整影片节奏的可能性。

Experiments with editing, specifically cutting, revealed that if properly integrated into a sequence, cuts could produce objective scenes in which the audience felt they were in the experience, but not directly inside the scene. Looking at the main action from a physical and emotional distance, rather that always feeling like they were directly inside of the action. Objective scenes allow the audience members to become close bystanders rather than feeling like the actions in the scene are happening directly to them.

通过对剪辑技术(尤其是剪切技术)的实验,研究人员发现,只要能将剪辑恰当地融入到一段镜头序列中,就能够创造出使观众感到“虽然身处故事之中,但并非直接置于场景之内”的客观场景。这种方式让观众能够在一定的物理和情感距离之外来观察事件的主要动作,而不会总是感觉自己正处于事件中心。通过构建这样的客观场景,观众会感觉更像事件的近距离旁观者,而非感觉一切事件都直接发生在自己身上。

Alternating between subjective and objective scenes allows emotional ebbs and flows in the structure of a show, so that producers can employ subjective techniques to “grab” or “fully immerse” the audience and objective techniques to offer the audience a safe distance from the impact of the scenes.

在主观和客观场景之间交替切换,可以在影片结构中产生情感的起伏。制作人一方面可以运用主观技巧来“抓住”观众或使其“完全沉浸”,另一方面可以运用客观技巧为观众提供安全距离,以减轻场面带来的冲击感。

Finding this balance is one of the most important keys to immersive storytelling on the dome. Misunderstanding and misusing these techniques are the quickest way to break the audience’s willing suspension of disbelief and pull them out of the experience.

这种平衡的把握,是全景球幕沉浸式叙事最关键的因素之一。如果误解或误用了这些技巧,就会很快让观众不再愿意放下怀疑,导致其脱离沉浸式体验。

一种不同的画框 A Different Kind of Frame

Ben Shedd called fulldome a “frameless medium,” which it is to a large degree; however, the audience is almost always looking up to some degree, even in a severely tilted (30º forward tilt) dome. The audience can also see below the edge of the dome and see the edges of the dome to either side of them when facing forward in a unidirectional dome (or even in a non-titled dome with omnidirectional seating). In most fulldome theaters, the audience is aware of at least the lower edge of the frame.

本·谢德(Ben Shedd)将全景球幕描述为一种“无框媒介”,这种说法在很大程度上是准确的。不过,观众在观看时几乎总会不自觉地抬头,即便在前倾角度多达30度的球幕中也不例外。这导致观众在观看单向球幕时可以看到球幕的下方和左右两侧边缘,在配备了全向座椅的非倾斜球幕中也是如此。因此,在大部分全景球幕影院中,观众至少能察觉到球幕的下边缘。

Domes also have the inherent challenge of needing lots and lots of image resolution, since the dome surrounds the audience on all sides, and half of the pixels are behind the audience. This causes the individual pixels themselves to be closer to the audience and larger than they would be if they were all out in front of them. Imagine an HDTV folded over the heads of each audience member. The pixels would appear too large and too close. For optimum resolution, more and smaller pixels are necessary. VR has a similar resolution problem, since even a “retina display” that is too close to the viewer appears to have large pixels and low resolution. This is why many modern fulldome theaters and shows have at least 6K × 6K resolution or even 8K × 8K resolution. The standard master frame for digital fulldome is a circular quidistant azimuthal fisheye with a 1: 1 (or square) aspect ratio. The circular fisheye frame is called a dome original or dome master (Figure 6). Dome master hemispherical sequences are typically produced at 4K × 4K (4096 x 4096 resolution) up to 8K × 8K (8192 x 8192 resolution) for each frame. Fully spherical scenes can also be mastered in equirectangular format (the standard frame format for VR production) at 8192 x 4096 for 4K spherical content or 16384 x 8192 for 8K spherical content.

球幕电影面临的一个主要挑战是对图像分辨率的极高要求。因为球幕将画面环绕在观众四周,有一半的画面实际上是位于观众背后的,这就使得画面的每个像素点相对于观众而言更大、更近。可以将其想象为将一个高清电视屏幕折叠起来,覆盖在每位观众头顶上,屏幕上的像素点会显得异常庞大且触手可及。要实现理想的画质,就需要使用数量更多、尺寸更小的像素点。VR 技术在分辨率方面也面临着相似的挑战,即便是非常接近眼睛的“视网膜显示屏”也会因为像素点过大而显得分辨率较低。这就是为什么现代全景球幕影院及其内容至少采用 6K × 6K 分辨率,甚至是 8K × 8K 的超高分辨率。全景球幕数字影像的标准母版画面采用圆形等距方位角鱼眼镜头(circular quidistant azimuthal fisheye)进行画面拍摄,这种画面具有 1: 1 的正方形宽高比,被称作球幕原版(dome original)或球幕母版(dome master)。球幕母版的半球形镜头序列通常以 4K × 4K(4096 × 4096)到 8K × 8K (8192 × 8192)的分辨率制作。全景球幕影片的场景还可以转制为虚拟现实(VR)常用的等距矩形(equirectangular)格式,用于制作 8192 × 4096 的 4K 球形影片,或 16384 × 8192 的 8K 球形影片。

Figure 6. The dome master or fisheye frame of digital fulldome

Source: Photo by Diego Delso, distributed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

Furthermore, standard 24 fps cinema frame rate looks “steppy” and appears to judder in the dome. Higher frame rate (HFR) capability smooths out the experience, especially for digital astronomy presentations. For pre-rendered shows, the standard fulldome frame rate is 30 fps, and for real time graphics, the standard frame rate is 60 fps. Higher frame rates up to 120 fps and higher are also possible 3D stereo fulldome is also possible, requiring additional technology in the theater to play back 3D and a complete dome original frame sequence of left eye frames and right eye frames at a rate of 60 fps per eye.

此外,标准的 24 fps 电影帧率,在球幕上看起来会有跳跃(steppy)和抖动(judder)感。高帧率(HFR)技术可以使观看体验更加平滑,对于数字天文学演示而言尤其如此。对于预渲染的影片而言,标准的全景球幕帧率是 30 fps,实时渲染图形的标准帧率则是 60 fps。120 fps 以上的更高帧率,以及 3D 立体全景球幕,在技术上都是可行的,这需要影院采用额外技术来播放 3D 影像,以单眼 60 fps 的帧率播放完整的球幕原版序列的左眼和右眼帧。

This resolution and HFR requirement can be a significant burden for producers especially when combined with fulldome 3D. 8K × 8K frames are four times the resolution of 4K × 4K frames, which are also four times the resolution of 2K × 2K (essentially HD) frames. This means that 8K frames take four times longer to render and are four times larger than 4K × 4K frames. HFR shows that play back at 60 frames per second require twice as many frames as a standard 30 fps show. Adding 3D doubles the number of frames that must be produced, since 3D requires a complete set of frames for the right eye and for the left eye. The math on this is staggering: each 8K × 8K file (uncompressed) would be approximately 192 MB. For 60 fps 3D, this would require 120 8K frames per second. At 192 MB per frame, this translates to 23 GB per second. The average length of a fulldome show is 22 minutes; therefore, a 22-minute 8K 3D 60 fps per eye show would require 79,200 frames per eye at a total data size of 15 TB per eye (uncompressed) or a total of 158,400 frames and 30 TB for such a show. This assumes no image compositing, or one layer per frame, which is not realistic given standard “layered” production workflows. Producing layered elements for each frame would make the production process even more daunting.

这种高分辨率、高帧率的要求,对制作人而言可能是一个重大负担,在引入全景球幕 3D 时更是如此。8K × 8K 帧的分辨率是 4K × 4K 帧的四倍,而 4K × 4K 帧的分辨率也是 2K × 2K 帧(和高清相似)的四倍。这意味着 8K 帧的渲染时间是 4K × 4K 帧的四倍,文件大小也是其四倍。以 60 fps 帧率播放的高帧率影片,需要比标准 30 fps 影片多两倍的帧数。增加 3D 放映会使需要制作的帧数翻倍,因为 3D 影片需要分别制作完整的左右眼帧的集合。在这种情况下,计算得到的数据量是惊人的:每个未压缩的 8K × 8K 文件大约为 192 MB,对于 60 fps 的 3D 影片,需要每秒 120 个 8K 帧。以每帧 192 MB 计算,这相当于每秒 23 GB。全景球幕影片的平均长度为 22 分钟,因此一个 22 分钟的 8K 3D 单眼 60 fps 影片需要每眼 79,200 帧,总数据量为单眼 15 TB(未压缩),双眼总计需要 158,400 帧,大小达 30 TB。上述计算只考虑了每帧仅一个图层、没有图像合成的情况,这在标准“分层”制作流程中是不现实的。为每帧画面制作分层元素,会使制作过程更加艰巨。

With this said, the results of 8K fulldome production can be truly astonishing, surpassing any other conventional form of media in terms of resolution, immersion, and raw impact. GPU based rendering technology has made 8K production more possible, but it is far from practical or cost effective at this time.

话虽如此,8K 全景球幕制作的成果确实令人惊叹,其在分辨率、沉浸感和原始冲击方面超越了任何其他传统媒体形式。基于 GPU 的渲染技术使 8K 制作成为可能,但目前远非实用,性价比也较低。

叙事工具 STORYTELLING TOOLS

Traditional cinema has a well-established collection of visual storytelling tools. These include the following:

传统电影拥有一套成熟的视觉叙事工具集,包括以下内容:

- Editing 剪辑

- Composition 构图

- Camera Movement 摄影机运动

- Actor Blocking 演员走位

- Color 色彩

- Light 光照

- Camera Angles 摄影机角度

- Lenses 镜头

- Special Effects 特效

- Many, many others 许多其它工具

Over 100 years, filmmakers have refined the uses of these techniques within the constraints of the medium.

在过去的一百多年里,电影制作人在这一媒介的限制内,不断精进每项技术的应用。

Two key attributes define the essential capabilities of cinema: the frame itself and editing. In traditional cinema, the frame itself is one of the most powerful tools filmmakers use to direct the audience’s attention and guide them through the story. The frame inherently restricts the audience’s view and perspective and only presents what the director wants the audience to see at any given time. Combined with skillful editing, the visual story ebbs and flows according to the director’s vision, focusing the audience exactly where they want it shot by shot, and scene by scene throughout the film. In traditional film, the frame confines, restricts, and contains the imagery within each shot. The art of editing transitions these pictures rhythmically and structurally, using shots as building blocks of the visual story. Editing combines shots with varying fields of view (wide shots to close ups), and the frame itself helps define the type of shot within it, since the subject in a close up fills more of the frame than the subjects in a wide shot.

在电影艺术中,有两个核心元素塑造了其独特的表达能力:画框本身,以及镜头的剪辑。在传统电影制作中,画框不仅是导演引导观众关注和体验故事的强有力工具,也是一种限定观众视角的自然手段,可以在任何特定时刻只呈现导演希望观众看到的内容。结合巧妙的剪辑,电影的视觉叙事随着导演的意图而起伏波动,逐个镜头、逐个场景地将观众的注意力牢牢吸引。在传统电影中,画框可以限制、约束、包含每个镜头内的影像。剪辑艺术通过有节奏和有结构的方式在这些画面之间过渡,将各个镜头有机组合成完整的视觉故事。剪辑将不同景别的镜头(从广角到特写)结合起来,而画框本身则协助定义了它所囊括的镜头的类型,因为特写镜头中的主体占据了更多的画面空间,而广角镜头中的主体则占据较少空间。

Also, in traditional cinema, the audience is looking at the film voyeuristically. Through empathy and emotional resonance, the audience may feel very connected to the experience, but they never feel that they are actually inside the film, since it clearly exists out in front of them. Surround sound and more advanced dimensional sound systems like Dolby Atmos, Fraunhofer, Iosono, Barco Auro, IMAX 12.0, and others envelop the audience with sound to help create a stronger sense of immersion.

此外,在传统电影中,观众是以一种偷窥的方式观看的。通过共鸣和情感共振,观众可能感到自己与这种体验之间建立了紧密的联系,但他们从不觉得自己真的进入了影片之中,因为画面显然存在于他们的视线前方,是外部的存在。而杜比全景声(Dolby Atmos)、Fraunhofer、Iosono、巴可 Auro、IMAX 12.0 等环绕声和更先进的多维声系统,则可以用声音包围观众,辅助创造更强的沉浸感。

With all of its storytelling power, however, traditional cinema cannot place the audience inside a scene.

虽然传统电影拥有强大的叙事能力,但它无法将观众置于场景之中。

全景球幕影片制作的挑战 FULLDOME FILMMAKING CHALLENGES

Fulldome filmmaking is inherently immersive, as previously described. The audience starts out inside the experience and remains immersed throughout the film. This effect can be very powerful, but there are many challenges to storytelling that this sense of presence and the medium itself creates.

如前所述,全景球幕电影制作本质上是沉浸式的。观众一开始就置身于体验之中,并且在整个电影过程中保持沉浸。这种效果可能非常强大,但这种临场感和媒介本身也带来了许多叙事挑战。

Here are just some of the challenges to storytelling in domes:

以下是在球幕中叙事的一些挑战:

演员在银幕上的大小 Size of Actor(s) on Screen

Because the dome evokes such a strong sense of presence inside a place, there is a natural expectation that objects should look the way they would appear in real life, especially when employing subjective camera techniques that anchor the audience in the scene as if they are actually there. Humans depicted on screen need to look scaled properly against their environments on screen, which is also true of traditional cinema, but in subjective scenes, the actors on screen should also feel properly sized relative to the theater screen and the audience. If a human on the dome appears too large aesthetically, they appear giant, and if they appear to be too small aesthetically, they seem to miniaturize. This seems particularly problematic, since dome sizes vary dramatically from venue to venue. In practice, however, if the human character feels right on the dome, any dome, the scale of the actor will work regardless of the dome size, since the angle of light emanating from the object on the dome will be the same whether the dome is very large or relatively small. Larger domes expand out equally in all directions, so everything scales up equally, appearing the same relative size. The converse is true of smaller domes. An interesting phenomenon, but it works consistently because of the applied physics of light and the equal curvature of the dome despite its size.

因为球幕唤起了如此强烈的临场感,人们自然期望物体看起来就像它们在现实生活中的样子。特别是当使用主观镜头技术时,观众会被锚定在场景中,仿佛他们真的在那里一样。球幕描绘的人类角色需要与球幕呈现的环境大小成比例,这与传统电影是一致的。但在球幕的主观场景中,球幕上的演员尺寸相对于实际球幕和观众的大小也应该是合适的。如果球幕呈现的人类角色在美学上设计得过大,就会看起来像巨人,而如果设计得过小,就会有微缩模型之感。这个问题似乎很麻烦,因为不同场所的球幕尺寸差异很大。但在实践中,如果人类角色在球幕上的大小看起来是自然的,那么无论球幕大小如何,这一比例都能产生合适的效果。这是因为无论球幕是大是小,球幕上的物体投射出的光线角度都是不变的。大型球幕在各个方向上均匀扩张,因此所有景物都会等比例放大,其相对大小看起来是一致的,而小型球幕同样遵循这一规律。这一现象十分有趣,它之所以能够如此一致地发挥作用,要归功于光的物理性质,以及球幕无论大小都保持相同表面曲率的特性。

The team that produced the fulldome show for New York’s Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum in 2000, did extensive compositing tests to determine the specific placement and scale of the on-screen actor who played the hansom cab driver who guided the audience through the history of New York City. It was key to the effectiveness of the attraction that the cab driver appeared to be the proper size relative to the immersive space.

在 2000 年为纽约杜莎夫人蜡像馆创作的全景球幕展示项目中,制作团队专门进行了一系列合成测试,旨在确定银幕上出现的出租车司机角色的位置和大小,这些角色起到引导观众探索纽约市历史的作用。确保出租车司机在视觉上与沉浸式环境的比例协调,是提升这一体验吸引力的关键。

剪辑 Editing

Cuts can work, but not in a traditional sense. Scenes built through inductive editing (lots of close ups) don’t usually work. The dome canvas creates too large and too wide of a view to achieve the same “restricted” view that closer shots provide in cinema when they are contained by the frame. There is no Psycho “shower scene” that exists in the fulldome medium any more than such a scene could exist on a live theater stage, at least not using traditional cinematic editing techniques.

在全景球幕影片中,剪辑的作用与传统意义上有所区别。通过归纳性剪辑(inductive editing)构建的包含大量特写镜头的场景,在球幕中通常不起作用,因为球幕画布的视野太大、太宽,无法实现电影中近景镜头所提供的“受限”视图。全景球幕媒介类似于现场演出剧院的舞台,不存在像希区柯克《惊魂记》“淋浴场景”那样的剪辑方式,或者说至少不会使用传统的电影剪辑技术。

Directors must creatively employ other techniques like camera movement, blocking and choreography in front of the camera, fades to black, and other methods borrowed from the world of theater to keep the audience oriented and anchored inside the virtual space as much as possible.

球幕影片的导演必须创造性地运用其他技术,比如摄影机运动、摄影机前的走位和编排、黑屏淡出等方法,这些方法借鉴自戏剧领域,其作用是尽可能保持观众的定位,将其锚定在虚拟空间内。

快速剪辑缺乏传统电影那样的吸引力 Fast Cuts Don’t Have Same Sizzle

There is a lot to see on the dome canvas that spreads across the audience’s field of vision. Fast cutting from one shot to another doesn’t give the audience adequate time to see what is in a given shot, since it is replaced quickly by another shot. According to Wired Magazine (https://www.wired.com/2014/09/cinema-is-evolving/) modern Hollywood films have an average shot length of 2.5 seconds. This type of cutting is way too fast for fulldome. Also, consider the similarity to a theatrical experience that the dome provides. Audiences can’t get up and rapidly shift from one seat to another every 2.5 seconds in the theater. That would be absolutely exhausting and ridiculous. Even with objective scenes on the dome, longer shots work much more effectively on the dome than shots that are less than 3 seconds in duration. With that said, a good rule of thumb is the less complex the shot, the shorter it can be on the dome (within reason). The more complex the shot, the longer it needs to be for the audience to perceive it properly.

在全景球幕电影制作中,由于球幕覆盖了观众的视野范围,观众需要足够的时间来观察每个镜头中的内容。从一个镜头切换到另一个镜头的快速剪辑,无法给观众足够的时间来观察特定镜头的内容,因为很快就会被另一个镜头所取代。根据《连线》杂志(Wired Magazine)的报道,现代好莱坞电影的平均镜头长度为 2.5 秒,这种剪辑速度对于全景球幕来说太快了。此外,考虑到球幕提供的类似于戏剧体验的环境,观众不可能像在剧院中那样,每 2.5 秒就从座位上站起来快速移动到另一个座位,那将是非常疲惫和荒谬的。即使是在球幕上的客观镜头,较长的镜头也比少于 3 秒的镜头更有效。因此,一个好的经验法则是,镜头越简单,它在球幕上的持续时间就可以越短,但要在合理的范围内。镜头越复杂,观众就需要越长的时间来正确感知它。

In traditional cinema, fast editing can add to the intensity and create a percussive rhythm to a scene; not so in fulldome. This type of editing is absolutely disorienting to the audience unless used sparingly for effect.

在传统电影中,快速剪辑可以增加场景的紧张感,并创造节奏感;但在全景球幕中并非如此。除非是为了特殊效果而小心使用,否则这种剪辑一定会让观众感到迷惑。

短镜头会导致理解困难 Short Shots are Hard to Read

Think of the dome as a portal to put the audience inside a shot that physically surrounds them. There is a complete and large hemispherical canvas of information for the audience to absorb and comprehend. Shots that are too short don’t give the audience time to orient themselves in the space of the film. If the goal is disorientation, then this technique can be extremely effective, but if disorientation is not the intent, it is best to give the audience time to be absorbed into the scene.

可以将球幕视为一个门户(portal),它让观众置身于一个物理上包围他们的镜头中。观众需要吸收和理解的是一个完整且庞大的半球形画布上的信息。时长太短的镜头无法给观众足够的时间,让他们在电影的空间中定位自己。如果创作者的目标是让观众迷失方向,那么这种技术会很有效,但如果不想让观众迷失方向,最好给观众留出足够的时间来被场景所吸引。

运动速度 Speed of Movement

Motion must be slowed down to feel correct and natural on the dome, compared to cinema and television, since a dome has more real estate to cover. Think of the fulldome canvas like being on the front row in a movie theater with a giant screen. Super-fast movements can be overwhelming. On a computer monitor, for example, if an object moves from one edge of a 27” screen to the other edge in 2 seconds, that movement may feel somewhat slow (a speed of 13.5” per second), but on a 60’ wide dome that same 2 second movement would move at a speed of 30’ per second: dramatically faster perceptually. This is not to say that fast movement isn’t possible on the dome. It is. It’s just vital to understand the acceleration effect the medium provides and to compensate for this accordingly.

与电影和电视相比,球幕上的运动必须放慢速度,才能感觉正确和自然,因为球幕有更多的空间需要覆盖。想象一下,观看全景球幕就像坐在巨幕影院的前排,过快的运动可能会令人晕头转向。例如,在计算机显示器上,如果一个物体在 2 秒内从一个 27 英寸屏幕的一边移动到另一边,那它的运动可能会感觉有些慢(运动速度为每秒 13.5 英寸)。但在一个 60 英尺宽的球幕上,同样的物体在 2 秒时间里移动的速度是每秒 30 英尺,在感知上明显会快得多。这并不是说在球幕上不能有快速运动——可以有,但至关重要的是,要理解媒介提供的加速度效应,并相应地进行补偿。

全景球幕画布 The Fulldome Canvas

The canvas itself is circular and distorted as if by a fisheye lens. As stated previously, this circular frame is often called the dome original or dome master. The center of the circle represents the top, or zenith, of a dome hemisphere with 0º tilt, or the spot directly above the audience. For tilted domes, this spot moves forward by the exact number of degrees the dome is tilted forward. For example, a dome tilted forward 30º will have the zenith point tilted 30º forward of the actual point that is directly above the audience’s heads. The bottom of the circle represents the front of the dome, the top of the circle represents the back of the dome, the left side of the circle is audience left, and the right side is audience right.

全景球幕画布本身是圆形的,并且像被鱼眼镜头扭曲了一样。如前所述,这个圆形框架通常被称为球幕原版(dome original)或球幕母版(dome master)。圆心代表了一个半球形球幕的顶部(top)或天顶(zenith),即直接位于观众头顶的 0º 倾斜点。对于倾斜的球幕而言,这个点会向前移动,与球幕向前倾斜的角度完全相同。例如,一个向前倾斜 30º 的球幕,其天顶点会向前倾斜 30º,偏离直接位于观众头顶的实际顶点。圆形的底部代表球幕的前部,顶部代表后部,左部是观众的左侧,右部则是观众的右侧。

One of the challenges of the production workflow when creating dome originals is that they are always visually distorted. Pixels compress near the zenith of the image and they stretch dramatically near the edges of the circular frame. Only when these images are projected inside the dome do they properly undistort by mapping to the three-dimensional geometry of the hemisphere itself.

在制作球幕原版的工作流中存在一个挑战,那就是这些原版在视觉上总是扭曲的。像素在图像的天顶附近被压缩,而在圆形框架的边缘附近则被戏剧性地拉伸。只有当这些图像在球幕内部投影出来时,它们才能通过映射到半球本身的三维几何形状而正确地“去扭曲”(undistort)。

It is imperative to screen material on the dome to determine and evaluate proper scale, placement, sense of motion, shot duration, etc. since these phenomena are virtually indistinguishable when watching playback of a fisheye preview on a computer monitor.

在球幕上实际放映影片是至关重要的,这样做是为了评估并确定适当的比例、位置、运动感、镜头持续时间等参数。相比之下,在计算机显示器上回放鱼眼预览时,这些现象是很难分辨的。

More experienced fulldome creators can get a good sense of how a scene is playing from a fisheye preview, but even seasoned professionals can miss important details if they don’t view their work on a dome.

有经验的全景球幕创作者可以通过鱼眼预览很好地感知场景的表现,但即使是经验丰富的专业人士,如果他们不在球幕上观看自己的作品,也可能会错过重要的细节。

真人实景摄影 Live Action Photography

Interestingly, the advent of Virtual Reality has contributed to the development of innovative new camera technology that allows filmmakers to capture real world imagery in 180º and 360º. In fact, there are significant parallels in processes between VR production and fulldome production. VR often requires a completely spherical image, but fulldome only requires half of that, a 180º hemisphere. Spherical VR cameras used for fulldome production offer filmmakers the flexibility to adjust the tilt and orientation of the spherical imagery for optimum placement on a non-tilted and a severely tilted dome without having to reshoot content for display on multiple types of dome configurations. The appropriately formatted hemispherical dome originals can be extracted from spherical equirectangular frames.

有趣的是,虚拟现实(VR)的出现促进了摄影机技术的创新发展,这项技术使电影制作人能够以 180º 和 360º 的视角记录现实世界的影像。实际上,VR 和全景球幕的制作流程有着显著的相似之处。VR 通常需要一个完全球形的影像,但全景球幕只需要一半,即 180º 的半球。用于全景球幕制作的球形 VR 相机为电影制作人提供了很大的灵活性,他们可以调整球形图像的倾斜角度和方向,从而在无倾斜(non-tilted)和大角度倾斜(severely tilted)的球幕上都能获得最佳呈现效果,而无需为了适配多种球幕类型而重新拍摄内容。从球形等距矩形帧(spherical equirectangular frames)中可以提取出格式正确的半球球幕原版。

There are modern cameras that have up to 4K vertical resolution, and for a majority of domes these offer enough resolution for the live-action imagery to look reasonably good on a 4K × 4K digital dome. The problem is that for the images to look as crisp and as realistic as possible, they really need to be produced at a higher resolution than 4K to allow pixel sub-sampling to optimize each pixel on the dome. Furthermore, 180º fisheye lenses cut off the horizon if they are pointed straight up during a shoot. Fisheye lenses with fields of view over 200º are needed to see below the lens and photograph the horizon below the camera.

现代摄影机的垂直分辨率高达 4K,对于大多数球幕来说,这足以使真人实景影像在 4K × 4K 数字球幕上具有很不错的观感。问题在于,为了使影像尽可能清晰和真实,实际上需要采用高于 4K 的分辨率进行制作,以便进行像素子采样,优化球幕上的每个像素。此外,如果在拍摄过程中采用 180º 鱼眼镜头直接指向上方,则地平线会被切断。为了看到镜头下方,并拍下摄影机下方的地平线,需要采用视角超过 200º 的鱼眼镜头。

A single 8K camera can be mounted on a Nodal Ninja, which is a camera mount that has built in nodal points around a shared center point, allowing a scene to be photographed multiple times from a fixed position. The camera points in a different direction for each take as the camera angle shifts from nodal point to nodal point until capturing all angles of a hemisphere or complete sphere. This technique can produce phenomenally high-resolution master frames: 16K × 8K spherical, but without computer-controlled tripods or dollys, all shots captured this way must be stationary with no camera movement at all. This technique provides ultimate resolution at the cost of camera movement.

可以将一台单独的 8K 相机安装在 Nodal Ninja 上,这是一种摄影机支架,围绕一个共享的中心点内置了多个光心点(nodal points),允许从固定位置多次拍摄同一场景。随着摄影机角度从光心点转移到另一个光心点,摄影机可以指向不同方向,直到将半球形或球形的所有角度都拍摄下来。这种技术可以产生极高分辨率的 16K × 8K 球形母版,但由于没有计算机控制的三脚架或轨道车,以这种方式拍摄的所有镜头必须是静止的,完全不能有摄影机运动。这种技术提供了成片的高分辨率,但以牺牲摄影机运动为代价。

Multi-camera rigs tend to integrate short focal length lenses in order for each camera to see the widest possible field of view. This reduces the total number of cameras needed for the rig and creates fewer recordings that will have to be stitched together to create the hemispherical or spherical imagery. Spherical cameras come in all shapes and sizes, from the GoPro Max with two fisheye cameras mounted back-to-back, to larger rigs containing multiple RED, ARRI, or other professional cameras in a spherical array, and everything in between including the Insta360 Pro camera, which is essentially a point-and-shoot spherical camera with multiple lenses and cameras imbedded around a sphere. Companies such as Radiant Images in Los Angeles specialize in these types of camera systems, offering a varied assortment of choices for purchase or rental.

多摄影机装置(multi-camera rigs)往往集成了多个短焦距镜头,使得每个摄影机都能看到尽可能宽广的视野。这种组合减少了装置所需的摄影机总数,也减少了为创建半球形或球形影像而需要拼接在一起的影像数量。球形镜头摄影机有各种形状和大小,从 GoPro Max 这样背靠背安装两个鱼眼镜头的设备,到包含多个 RED、ARRI 或其他专业摄影机的大型装置,以及介于两者之间的 Insta360 Pro 相机,它本质上是一种将多个镜头和摄影机嵌入一个球体周围的即拍式(point-and-shoot)球形摄影机。洛杉矶的 Radiant Images 等公司专门经营这类摄影机系统,提供了购买或租赁的多种选择。

Stitching software to combine images from each camera into a unified spherical image is often rather primitive and requires considerable physical tweaking and painstaking adjustments to optimize and master an image that looks seamless. Additionally, the physical layout of the cameras in the spherical rigs creates dead zones in the spaces between cameras in the rig especially if a subject comes too close to the camera rig. Choreography in front of a spherical camera must be carefully orchestrated to keep actors and key objects far enough from the rig to prevent them from splitting apart visually across the seams between the cameras in the array.

拼接软件(stitching software)用于将每台机器拍摄的图像合并为一个统一的球形图像。这种软件通常相当原始,为了优化并制作一个无缝的影像母版,需要进行费时费力的物理调整。此外,球形装置中摄影机的物理布局导致摄影机之间的空间存在拍摄死角,当被摄对象离装置太近时,死角会更加明显。在球形摄影机前方设计走位编排时一定要谨慎,需要让演员和关键物体远离摄影装置,以防它们在摄影机阵列之间的接缝处产生视觉上的断裂。

Lens selection is also extremely limited for fulldome live action photography. Traditional cinematographers rely on a variety of lenses to produce visual aesthetic effects to structure the depth of field (how much of the background is in focus) and field of view (how much the audience can see inside the frame). In fulldome photography, the audience generally sees everything, since the imagery inherently surrounds them, and generally everything is in focus deep into the frame.

在进行全景球幕真人实景摄影时,可用的镜头选择也非常有限。传统电影摄影师会利用各种镜头来创造特定的视觉效果,比如调整景深来控制背景的清晰度,或是通过调节视角范围来决定观众所能看到的画面范围。然而,在全景球幕摄影中,观众几乎能够看到每一个角落,因为影像本质上是将观众环绕其中的,画面内的元素通常都处于清晰聚焦的状态。

Of course, filmmakers may also choose to shoot live action elements in front of a green screen with traditional video cameras, and then composite these assets into hemispherical CG environments using fulldome production tools produced by Evans & Sutherland, Sky-Skan, Multimeios, and others.

当然,电影制作人也可以选择在绿幕前使用传统摄影机来拍摄真人实景元素,然后使用 Evans & Sutherland、Sky-Skan、Multimios 等公司生产的全景球幕制作工具将这些资产合成到半球形 CG 环境中。

Filmmakers must consider and navigate the complexities of the fulldome technical workflow in order to deliver shows on time and on budget.

电影制作人必须考虑并测试全景球幕技术工作流程的复杂性,以便在预算内按时交付成片。

Figure 7. An 8mm focal length fisheye lens.

Source: Photo by Jud McCranie distributed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

For single camera production, there is one type of lens: the fisheye (Figure 7) that captures a single view that is 180º to 250º wide. Fisheye lenses are the least flattering lenses for people since their extreme optics will severely distort objects that come too close to the lens, creating an unflattering effect known as foreshortening (Figure 8). The part of an object that is close to the camera appears extremely large while parts of the object further away appear unnaturally small. This is especially disastrous with human faces, since noses and chins can become enormous relative to the rest of the face when a person is too close to the lens.

对于单一摄影机的拍摄而言,有一种类型的镜头:鱼眼镜头(见图 7),它捕捉到的单视角宽度为 180º 至 250º 。鱼眼镜头是对人物拍摄而言最不讨好的镜头,因为它们极端的光学特性会使距离过近的景物严重扭曲,产生一种被称为透视缩短(foreshortening)的令人不舒服的效果(见图 8)。物体靠近摄影机的部分会显得非常大,而远离摄影机的部分则显得不自然地小。这对于人脸而言更加具有灾难性,因为当一个人离镜头太近时,其鼻子和下巴相对于脸部其他部分可能会变得巨大。

Figure 8. Foreshortening effect caused by being too close to a fisheye lens

Source: Dr. Denny Vrande č i ć, distributed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

Fisheye lenses also have infinite depth of field, so everything is always in focus, removing one of the classic cinematic techniques that shallow depth of field allows: blurry backgrounds. Soft focus in the background and sharp focus on the subject draws the audience’s attention to the subject that is in sharp focus and away from the soft-focus background. This technique facilitates moments in which the director wants to amplify the emphasis on the subject and minimize distractions. Live action lenses for digital fulldome can’t do this, so directors must employ other techniques to direct the audience’s focus and attention.

鱼眼镜头还具有无限景深,因此所有东西总是在焦内的,这就消除了浅景深所允许的经典电影手法之一:背景模糊,即将背景放在焦外,将主体放在焦内,将观众的注意力引向清晰聚焦的主体,远离柔和聚焦的背景。这种技术有助于导演强调主体,排除主体之外的干扰。全景球幕的真人实景镜头无法做到这一点,因此导演必须采用其他技术来引导观众的焦点和注意力。

Current digital transforms developed to stretch and warp 4: 3 aspect ratio produced by 15/70 IMAX film enable flat screen imagery to cover 80% of the dome (as IMAX Dome systems have done since the 1970s). Live action footage can be shot with any lens in 4: 3 aspect ratio and then warped to the dome. This technique leaves a 20% gap of black in the back of the dome that needs to be filled in with CGI or just feathered to black. This workaround allows cinematographers access to essentially any lens, letting them break free from constantly having to choose a fisheye or wide-angle lens.

当前开发出的数字处理技术,能够调整和适配由 15/70 IMAX 胶片拍摄的 4: 3 宽高比的影像,让这些影像能覆盖球幕的 80%,这种做法自 1970 年代 IMAX 球幕系统以来就已经在使用。现在,摄制组可以用任意 4: 3 宽高比的镜头拍摄实景画面,然后将其适配至球幕银幕。这个技术处理过程会在球幕的后部留下大约 20% 的未覆盖区域,这部分通常需要通过计算机生成图像(CGI)来填补,或者简单地渐变到黑色。这种技术规避了之前电影摄影师常常面临的只能选用鱼眼或广角镜头的限制,现在他们可以自由选择各种镜头,为电影制作带来更多的创意空间。

A dome is a very challenging environment for projection. Because light falls on every part of the dome, the light from the back of the dome bounces back toward the front, scattering light into the dark areas of the scene, thereby reducing the contrast. This phenomenon called cross-reflection has a similar effect to what happens in a movie theater when the house lights come on during the credits roll at the end of the film. Blacks on the screen turn gray, and the contrast ratio of the image drops dramatically. LED domes are self-illuminating, solving the cross-reflection problem, producing bright images with phenomenal contrast. Currently LED domes are quite expensive, but as with all new technology, its price will drop and become more affordable over time.

球幕是一种极具挑战性的投影环境。因为光线会落在球幕的所有位置,球幕后部的光线会反射回前方,将光线散射到场景的暗区,降低画面对比度。这种现象被称为交叉反射(cross-reflection),与电影放映结束时观众席灯光亮起、银幕上黑色变灰、画面对比度急剧下降的效果类似。自发光的 LED 球幕解决了交叉反射问题,可以产出具有惊人对比度的明亮图像。目前 LED 球幕相当昂贵,但就像所有新技术一样,其价格随着时间的推移会不断下降,使场馆更加负担得起。

There is also only one perfect seat in the dome, and that is right in the middle, right under the zenith. This is the only place where all the images perfectly unwrap from their distorted dome original to look straight and undistorted on the dome. Anywhere else in the dome, vertical lines will curve. It’s simply a physics problem. Domes are compound curves, and they are curved everywhere. Domes warp everything, so directors need to be careful of straight lines. They won’t stay straight. This isn’t always a problem, but it is something to consider when designing an experience for an audience.

在全景球幕影院中,唯一能够得到完美视觉体验的座位是球幕天顶下方的中心位置。只有在这个位置,所有的影像才能从它们在球幕原版上的扭曲状态中完美地恢复过来,呈现为直线和未经扭曲的形态。在球幕的其他位置,观众会发现垂直线条呈现出曲线形态,这是由球幕的复合曲面结构所固有的物理特性导致的。球幕的每一处都是曲面,这意味着它会扭曲所有的图像,因此在设计球幕影院的视觉内容时,导演们需要格外注意保持影像中的直线,因为它们在球幕上不会保持直线状态。虽然这个问题并非总是存在,但在为观众设计沉浸式体验时,确实是一个需要考虑的重要因素。

数字全景球幕中的关键视觉叙事工具 KEY VISUAL STORYTELLING TOOLS FOR DIGITAL FULLDOME

The following list of tools work extremely well to help craft visual stories in the fulldome medium. By using these techniques separately and together, directors can tell amazing stories despite the aforementioned limitations of the fulldome medium.

以下技术手段非常适合帮助创作者在全景球幕媒介中打造视觉故事。通过单独或组合使用这些技术手段,导演可以克服上述全景球幕媒介的限制,讲述令人惊叹的故事。

构图 Composition

The arrangement of items across the fulldome canvas is one of most powerful resources in the director’s toolkit. There is an expansive world to paint both in terms of the imagery that surrounds the audience, but also what exists overhead. The fulldome canvas is surprisingly supple and can easily take the shape of the environment placed around it. Low ceilings and close walls can simulate a confined space; conversely tall trees stretching high above the audience can create the strong sensation of an expansive space. Many of the other tools below, except for the last two, work within the composition of the scene to create show’s visual aesthetic. More than virtually any other medium, fulldome does not have an obvious point of focus or place to look; therefore, it is imperative to skillfully and constantly guide the audience’s attention and visual focus throughout a show. The techniques below are some of the time-tested methods that can do just that.

在全景球幕画布上合理地安排物体的位置,是导演工具集中最强大的资源之一。球幕提供了一个可以绘制的广阔世界,不仅有围绕在观众四周的景象,还有观众头顶的空间。全景球幕画布具有惊人的灵活性,能够轻松地适应并展示周围环境的各种形态。例如,通过营造低矮的天花板和紧邻的墙壁,可以制造出压抑的空间感;而通过描绘高耸入云的树木,可以给观众带来一种开阔空间的浩瀚感受。除了下文提到的最后两种工具外,其他许多技巧都是在场景构图内使用的,可以协助打造影片的视觉风格。与其他媒介不同的是,全景球幕影院没有一个固定的观察焦点,因此在整部影片中精心且持续地引导观众的视线和注意力是十分关键的。以下提到的一些方法经过了时间的考验,有助于达成这一目标。

摄影机运动 Camera Movement

Moving the perspective of the entire scene, crafting dynamic and changing compositions by moving the camera, provides visual interest to scenes, allowing them to develop over time and stay on screen longer without the need for cuts. The more the scene can change within the shot and the camera’s choreography, the more the audience will stay anchored within the location or place of the scene.

可以通过移动摄影机来变化整个场景的视角,打造动态和变化的构图,为场景提供视觉兴趣点,使场景随时间发展并在银幕上停留更长时间,而无需使用剪切。单镜头内场景和摄影机的编排变化越多,观众就越能持续沉浸在场景所展现的位置或场所中。

Camera movement must be handled skillfully, since the audience often feels that they are actually moving with the camera through the scene. It is quite a powerful kinetic connection that immersion creates in the audience.

摄影机的运动一定要把握恰当,因为观众经常感觉他们实际上是随着摄影机在场景中移动的 。这种由沉浸感带来的动感连接(kinetic connection)对观众而言极具吸引力,是一种很有力的手段。

Just like any technique this can be underused and overused. Some notable fulldome films are comprised of one continuous shot over their 20 to 25-minute running time. This can be quite effective, but also has the unexpected complication of forcing the camera path over time into dead moments that have to be enhanced to liven them up (much like long stretches of open highway on an endless road trip) or to restricting your view to what can logically fit along that unbroken camera path. Intentionally leading with a technique or gimmick can diminish the overall creative possibilities and highlight the technique at the expense of the impact of the overall experience. Everything in moderation, unless there is a compelling creative reason to lean heavily into one technique or another. It’s a delicate artistic balance that the director must constantly evaluate.

正如任何制作技巧一样,全景球幕电影中的单镜头技术手段可能被低估,也可能被滥用。有些知名的全景球幕影片仅通过一段 20 至 25 分钟的连续镜头来叙述整个故事。这种方法虽然有其独到之处,却也带来了特有的挑战,例如可能会导致画面在某些时段显得缺乏活力,需要通过额外的手段来增添生气(就像长途驾驶中穿越漫长而单调的公路一样);或者限制了故事视角,只能沿着连续的镜头路径逻辑安排场景和事件。如果片方有意过分依赖某一技术或噱头,可能会限制创作的广度和深度,使得技术本身成为观众的焦点,而忽略了作品整体的情感影响。因此,除非有充分的创意理由来支持某种手法的重度使用,否则还是应该保持技术使用的适度平衡。这需要导演不断地进行审慎考量,以维持艺术创作的微妙平衡。

演员走位 Actor Blocking

Just as in a stage play, blocking helps define the scene’s action and the actors’ characters. Whereas a pure theatrical experience is limited by the confines of the available performance areas inside the theater, in a fulldome show, actors can appear and move anywhere within the immersive canvas. This needs careful balance as well, but in a dynamic shot, even if the camera is stationary, actors moving toward and away from the camera or moving through the scene can help guide the audience’s attention within a frame that has no clear director or point of focus. As humans, we like to look at other humans, and our eyes follow them throughout a scene. This is a powerful way to guide the audience’s gaze inside the frame, which is more crucial than ever considering the inability to use traditional cinematic editing to restrict the audience’s view.

就像在舞台剧中一样,在全景球幕中,演员的走位也是同样关键的。传统剧场表演受限于剧场内的表演空间,全景球幕影片则打破了这些限制,允许演员在整个沉浸式空间自由移动。这种自由虽然提供了更多可能性,但也需要精心平衡,以确保动态场景中的演员动作——无论是向摄影机移动,远离摄影机,还是穿梭于场景之中——都能在一个没有固定观察焦点的空间里,有效地吸引并引导观众的注意力。作为人类,我们喜欢观察人物的动作,我们的眼睛会跟随人物在场景中的移动,这种关注成为引导视线的强大工具。在不能依靠传统剪辑技术来限制观众视野的全景球幕环境中,利用人物动作来引导观众的视线比以往任何时候都更为关键。

画面内的移动 Movement Within Frame

The human eye also follows movement. Objects that move against others that are stationary grab attention. Something that moves causes humans to want to know what is moving, where it is going, and what it may be up to. This could relate to simple survival skills or basic curiosity. Either way, object movement inside the frame is a highly effective way to guide the audience’s attention through the expansive fulldome canvas.

除了跟随人物之外,人眼也会跟随移动的物体。当物体相对于其他静物产生移动时,会吸引观众的注意力。观众会好奇,在移动的是什么物体,它要去往哪里,可能会做什么。这可能与我们的生存本能或基本的好奇心有关。无论如何,恰当设计画面内物体的移动,都是在广阔的全景球幕画布上引导观众注意力的高效方式。

画面的视觉平衡 Visual Balance of Frame

Humans seem to have a desire for order and organization. Even a picture that is slightly off of perfect level screams out to be adjusted. Visual balance in a fulldome frame is no exception. Similar objects or those that have a symmetrical layout on screen are easily ignored, but anything that stands out because of its size (smaller or larger than other objects) or because of its visual isolation within the frame draws focus. This orchestration of visual balance is not nearly as powerful as movement or a human in the frame, but the choreography of visual elements and the balance of their visual symmetry and asymmetry can cause viewers to look at the objects that stand out. This is pure visual composition and the creation of an area of interest inside the fulldome frame and is most analogous to composition principles in conventional cinema.

人类天生就倾向于寻求秩序和组织,哪怕是略微不居中的画面也能引起我们调整的冲动。这种对平衡的追求在全景球幕电影中同样适用。虽然相似物体或对称布局在银幕上容易被忽略,但那些因大小差异(无论是更小还是更大)而在画面中显得孤立的元素,却能够自然吸引观众的注意力。对视觉元素的精心排布,以及视觉上对称与非对称的巧妙平衡,可以有效引导观众关注那些突出的元素。这样的视觉构图不仅在全景球幕电影中创造了引人注目的区域,其精髓与传统电影中的构图原则也不谋而合。

色彩 Color

In a similar way, color asymmetry can cause the audience to focus on colors that look different or draw attention. For example, a green object will pull focus in a scene that is largely blue. Humans are very aware of differences, and unique colors in a scene will stand out. Also, warm colors (reds, yellows, oranges) command attention and push to the foreground while cool colors (blues and purples) recede and move to the background. Greens are neutral and can serve either purpose. White and black can switch roles based on the surrounding colors. In other words, either black or white can be dominant or recessive based on the context of the scene. With that said, white tends to grab our attention more than black if all other factors are neutral.

同样,颜色的不对称使用也可以有效引导观众的注意力,特别是那些在场景中显得与众不同或突出的颜色。举个例子,一个绿色物体在以蓝色为主的场景中会特别引人注目。人们对颜色的差异极为敏感,场景中的独特颜色自然会成为焦点。此外,暖色系(如红、黄、橙)往往能够吸引观众的视线并凸显于前景,而冷色系(如蓝和紫)则倾向于退缩到背景之中。绿色居于中立位置,可根据需要发挥前景或背景的作用。白色和黑色的视觉效果则会随着它们所处的颜色环境而变化;换言之,它们可以根据场景的具体情境表现为主导或是辅助的角色。尽管如此,若其他条件保持中性,白色通常更容易吸引人们的注意力。

光线 Light

Human eyes are basically light receptors. Light activates sight. Light on objects in a scene makes people look at them. It’s the same reason people follow the beam of light from a flashlight in the dark, even if it isn’t illuminating anything interesting. Light directs the viewer’s attention very powerfully. Once again this is a time-honored tool from the beginning of cinematography and theater. Lighting is a very useful too that can guide the audience attention throughout a show.

人眼本质上是对光线的反应器(receptor),光线唤醒了我们的视觉。在场景中,物体被光照亮时,便自然吸引了我们的目光,这就像人眼视线在黑暗中自动跟随手电筒光束一样,即便它并未照亮任何引人注目的物体。光线是引导观众视线的一个非常强大的手段,这个方法自电影和戏剧艺术的初期便被广泛使用。光影是极为有效的工具,能够在影片中持续地吸引和引导观众的焦点。

视觉简单性与复杂性 Visual Simplicity vs. Complexity

As much as humans like to think they are very complex and sophisticated, they default to what is simple and easy to understand. The human eye may be fascinated by complex imagery but will always try to simplify it or find the least complex place to look. This is why tunnels work so well on the dome. The audience looks right down the center of the tunnel to see where it is leading. The choreography and interplay of simple and complex visual structure can effectively show the audience exactly where to look in a scene. This can be everything from a tunnel to an alleyway blocked by tall buildings on both sides, to the tracks on a rollercoaster.

虽然人类倾向于认为自己非常复杂和精致,但在面对视觉信息时,我们往往会本能地寻找简单和直观的元素。即便复杂的图像能够吸引我们的眼球,我们也会不自觉地试图将其简化,寻找视觉上最不复杂的焦点。这解释了为何隧道场景在全景球幕电影中格外有效——观众的视线会自然地被隧道中心所吸引,并探索其通往的方向。通过巧妙地安排简单与复杂的视觉结构,可以清晰地告诉观众在场景中应当关注的位置:从隧道到被高楼环绕的小巷,再到过山车轨道,都是引导观众视线的有效手段。

向量 Vectors

Vectors are imaginary lines that point in certain directions within a frame. These cause the audience to look in the direction the vector is pointing or moving. Vectors on the dome can be caused by graphical composition where a line or curve forms from the spatial arrangement or simple patterns among a complex scene as described above. These are known as graphic vectors, which tend to be subtle. Other vectors that point in a certain direction, like an arrow, a street sign, or a finger pointing at something are called index vectors. These are a bit more powerful than graphic vectors. Finally, there are motion vectors where an object is moving in a direction, and the audience watches with interest where it is going. Motion vectors have the most weight and ability to direct the audience’s eyes through the scene.

向量(vector),或称作画面中的引导线,是指导观众视线朝特定方向移动的虚拟线条。球幕上的向量根据其形式分为几种类型:图形向量(graphic vectors)源于场景中的图形构图,其线条或曲线由复杂场景中的空间排列或简单模式构成,引导效果较为轻微;指示向量(index vectors)是指向特定方向的向量,如箭头、路标或指向某物的手指,其引导作用比图形向量更强;运动向量(motion vectors)则是通过物体的移动方向来吸引观众关注,这种向量在引导观众视线穿过场景方面,具有最大的权重和最佳的效果。

演员的视线 An Actor’s Eye Line

This is a specific type of vector generated by an actor looking in a particular direction on the screen. Wherever the actor looks, the audience is compelled to look as well. Part of this likely springs from innate curiosity; part may result from the fact that looking at something is a less obvious form of pointing. For this vector to work most effectively, the actor should look at something in the scene. This way the audience can follow the actor’s gaze to a landing point within the frame.

在全景球幕电影中,演员的目光方向本身就是一种强有力的向量——演员看向哪里,观众也会被吸引着看向哪里。这种现象可能部分源于人的好奇本性,另一个原因则是在我们的认知中,“注视某物”是一种比较含蓄的“指向”方式。为了充分利用这一效应,在设计场景时应让演员的目光停留在某一画面元素上,从而引导观众的视线聚焦于该点。

There is little offscreen space in fulldome, since the frame is so vast, but it is possible to use clever editing to connect the actor’s eye line from inside one shot into an object in the next shot.

全景球幕画面非常广阔,几乎没有画外空间,但可以通过巧妙的剪辑,将演员的视线从一个镜头连接到下一个镜头中的对象。

剪辑和场景过渡 Editing and Scene Transitions

As previously discussed, editing is possible and often necessary in digital fulldome. Editing allows directors to shift between subjective and objective scenes and to change the audience vantage point within an objective scene. Editing can also transition between subjective sequences to string larger sections of a film together.

如前所述,剪辑在数字全景球幕中是可行的,也往往是必要的。剪辑允许导演在主观和客观场景之间转换,并改变观众在客观场景中的视点。剪辑还可以在主观镜头序列之间过渡,将电影的主体部分串联起来。

There is no shortage of authoritative reference material for cinematic editing techniques, and there is neither space nor need to delve into these in this chapter. Suffice it to say that most time-honored principles of traditional editing still apply to digital fulldome, even if the frame or the immersive medium itself does not respond the same way as a cinematic frame that sits out in front of the audience. Experimentation and careful shot/sequence planning is essential to discover what can work the most effectively in a given project.

对于电影剪辑技术,权威的参考资料从来都是充足的,在本章中我们既无必要也无空间深入探讨这些技术细节。可以说,那些历经时间考验的传统剪辑原理,在数字全景球幕这样的新媒介上依旧适用,虽然这种沉浸式媒介的表现形式和直接呈现在观众面前的电影画面有所不同。要想在特定的项目中找到最有效的表现手法,有必要多进行实验,精心规划每个镜头和及其序列组合。

When used most effectively, cuts can become largely invisible and feel completely organic to the visual story. This places pacing and scene sequencing back in the hands of the director even in the fulldome medium.

当剪辑手法得到了有效的应用时,剪辑对观众而言可以变得近乎隐形,并且完全自然地融入视觉叙事中,这使得导演即便在全景球幕这一新媒介中,也能有效掌控叙事节奏和场景镜头序列。

声音设计 Sound Design

Audio cues are extremely effective in grabbing the audience’s attention, especially in moments where the director wants the audience to look up, to the sides of the screen or behind them toward the back of the dome. Even though fulldome is an immersive medium with 360º imagery, when an audience is seated, they typically look forward unless there are reasons for them to look elsewhere. Sound cues are an organic and elegant way to help direct the audience’s attention to different parts of the dome. This technique must be used gently, because it is uncomfortable for the audience to require them to move their bodies around to physically look behind them, especially when they are in a seated position. Better to use sound in the back of the dome to bring in something that quickly moves to the sides of the dome or across the zenith, such as a spaceship entering from behind and moving overhead. In this example the audience will only have to look up as the ship is passing above them.

声音提示(audio cues)在吸引观众注意力方面格外有效,尤其是当导演想让观众抬头看,向球幕两侧看,或者转身向球幕后方看时。虽然全景球幕以其 360° 全景图像为特色,属于沉浸式媒介,但坐着的观众通常会默认朝前看,除非有特别的理由吸引他们转到其他方向。声音提示便是一种自然且雅致的手段,用以引导观众的视线转移到球幕的不同区域。应用这一技巧时需要特别注意,因为让观众在坐着的状态下转身向后看可能会引发不适感。更理想的做法是,在球幕后方使用声音效果,吸引观众将注意力移向快速穿过球幕侧面或正上方的物体,比如一艘从后方出现、飞越头顶的宇宙飞船。这样,观众仅需仰头便可观察到飞船从上方经过的壮观场面。

The tools highlighted above can help directors navigate and craft the visual story for maximum impact, while avoiding the pitfalls of immersive media.

以上提到的技术可以帮助导演在创作视觉故事时,最大限度地提升影响力,并巧妙地避开沉浸式媒体可能遇到的陷阱。

有效的全景球幕叙事示例及分析 EXAMPLES AND ADVANTAGES OF EFFECTIVE FULLDOME STORYTELLING

The immersive fulldome canvas is not inherently better than traditional flat screen cinema, but as explored in this chapter, it is inherently different. In addition to the variety of specific aesthetic effects immersive content provides, fulldome creates a unique connection with the audience. They feel like they are inside the story, sometimes in first person point of view (POV) and other times in third person POV, but in both cases they are watching from inside the story as opposed to watching as a voyeur in traditional cinema where the audience is outside the experience looking in through the frame.

全景球幕技术并不自然而然地优于传统平面电影院,但正如我们在本章探讨的,它本质上具有不同的特质。全景球幕不仅提供了一系列独特的美学效果,更与观众建立了一种独特的连接。观众会有身临其境的感觉,有时是从第一人称视角(POV)体验故事,有时则是从第三人称视角。无论哪种方式,他们都是从故事内部观看的,而非像传统电影观众那样,作为一个外部的旁观者通过画框观看。

There are a host of films produced specifically for the fulldome medium that have leveraged these principles effectively within certain scenes and in some cases throughout the films.

有一系列为全景球幕特别制作的影片,将上述原则有效地应用在部分场景甚至全片当中。

- Microcosm: The Adventure Within: (Daut, 2002). The first science fiction and non-astronomical fulldome film ever created (written, produced, and directed by the author) was also the first time that a fulldome film moved from entirely a first person POV and made extensive use of cinematic editing to propel the story and change audience perspective in the immersive space. What started as a grand experiment actually helped define and clarify modern fulldome cinematic techniques.

《微观世界的奇幻旅程:深入探索之旅》 (Daut, 2002)。这部影片开创了科幻领域内的一项里程碑:它不仅是首部非天文主题的全景球幕电影(由作者本人担任编剧、制片、导演),还首次在全景球幕影院中运用了第一人称视角,通过电影式的剪辑手法来推进故事情节,并变换观众在沉浸式环境中的视角。这场宏伟的实验最终成为现代全景球幕电影技术发展的一个关键转折点。

The conceit of the film placed the audience inside a human-crewed submersible that could shrink down to microscopic size for injection into the bloodstream of a dying patient. After an introduction that set up the scenario, the audience finds themselves inside the submarine’s cockpit looking out the front window with controls and hardware of the submarine’s interior surrounding them. The show established this as the first person POV for the entire show. Rather than anchoring the entire experience inside the sub, the perspective cuts to a view outside the sub, watching the scene from within the scene from a third person POV. This change in perspective within a scene enabled editing to allow the viewer to move easily from one POV to the other; in fact, from the third person POV, cuts from shot to shot were easier to achieve because of the aesthetic distance created by the third person POV. This continuous sense of presence in the scene creates a dynamic effect that could not be possible in a traditional cinematic experience.

电影的创意是,让观众置身于一艘由人类驾驶的、能够缩至微观大小的潜艇内,并将潜艇注射进濒死病人的血流中。随着情节的展开,观众仿佛亲自坐在潜艇的驾驶舱内,透过舷窗向前看,周围环绕着潜艇内部的控制面板和设备。本片通过这样的设计确立了观影过程中的第一人称视角,同时不仅局限于潜艇内的体验,还巧妙地转换到潜艇外的第三人称视角,让观众既能在场景内部感受故事,又能从外部观察。这种视角的变换让剪辑过程更加流畅,使得观众可以轻松地在不同的视角之间切换。正是这种在场景中持续不断的临场感,营造出了一种动态的视觉效果,这在传统影院体验中是难以实现的。

- Microcosm: Stars of the Pharaohs: (Murtagh & Daut, 2004). This film broke ground with its stunning recreations of temples and tombs of ancient Egypt including the temple of Denderah (built in 3D as a photorealistic representation of how it exists today in its partially ruined state) and the temple of Luxor (built in 3D as a depiction of how it may have looked 3,000 years ago). By establishing a first person POV, the audience was allowed to travel inside these amazing locations in such a way that they felt transported not only to Egypt, but also back in time on a walk-through of these astonishing destinations. Traditional cinema does not allow this sensation of transportation inside virtual worlds.

《微观宇宙:法老之星》 (Murtagh & Daut, 2004)。这部作品通过精致再现古埃及的寺庙和墓穴,如丹德拉寺庙(用 3D 打造,呈现其今日残破的真实面貌)和卢克索寺庙(用 3D 展现其 3000 年前的可能样貌),开辟了球幕影像的新境界。通过采用第一人称视角,观众仿佛被带到了埃及,不仅跨越了空间,更穿越了时间,亲历了这些令人叹为观止的地点。这种仿佛置身虚拟世界的感受,是传统电影无法提供的。